“As Far as the Eye Can See”, this lettering, one of the most famous works by the artist Lawrence Weiner, would probably have to be called an icon. It’s so simple: a row of capital letters on the wall, outlined in black, painted in red, they look a bit like a football shirt, but – because they dominate the outer wall of the Queens Museum – must be meters high. The sentence, which gives the thoughts a lot of space, makes the world wide, but alludes in the same breath to the limitation of all human perception. And it sounds less like poetry than as if everything had been scraped away from the language until only the truth remained.

The artist also had this line painted in black on a white gallery wall. And printed in yellow on the cover of a catalog. Because that was the artist’s creed: first of all, it is about the thought. And only then about the execution. That is why Lawrence Weiner, born in the Bronx in New York in 1942, was considered one of the founders of conceptual art. And until his death on Thursday he persisted in their immateriality, their wisdom and breadth.

His first work was craters formed with explosives in a national park

Lawrence Weiner, whose father owned a small candy store in the Bronx, had to toil in the New York docks at the age of twelve to get the family through. And became an artist when he decided one morning not to go to work any longer, after school, but to the studio. By then he had already completed his first work, the “Cratering Pieces”. Even if at that time hardly anyone recognized a series of explosions in the Mill Valley National Park as such. In retrospect, however, the craters formed with TNT in 1960 must even be considered a very early land art piece. However, Weiner pointed out to the critic Benjamin Buchloh, who spoke to him about it in an interview, that he was by no means as radical and revolutionary at the time as art historians assess him. “I was just an 18 year old boy.”

The boy then began to paint, despite all reservations about the relationship between the artist and society. And painting wasn’t exactly his profession either. “But I knew that I definitely wanted to stick to the artist’s lifestyle, if only because it was a much better lifestyle than the lower middle class I came from.” Lawrence Weiner sought proximity to the avant-garde, hitchhiked to the City Lights bookstore in San Francisco or met beat poets like Jack Kerouac in New York bars.

His oeuvre also includes artist books

It was then also the language that was to become his medium. Which, as a sculptor, he added to the well-known media – stone, wood, metal, clay. First the three sentences of his “Declaration of Intent”, which he formulated in 1968. The conceptual art manifesto was short. A work of art, it is said, can firstly be made by the artist, but secondly, also by someone else. Or, third, it doesn’t have to be done at all. The announcement became the basis of an oeuvre that sometimes included objects, video films and performances – but also artist books. The “Statements” published in the same year, in which several projects are described, is still considered to be one of the most influential artist books ever. Harald Szeemann immediately invited the young American to the epochal exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form” in Bern.

And while Lawrence Weiner, who lived for years on a houseboat in Amsterdam with his wife and little daughter (out of financial difficulties, not out of romance, as he made it very clear), became more and more famous in Europe, was invited to the Documenta four times and to biennials and solo exhibitions, he had to wait a long time for recognition in his home country. Only in 2008 did the Whitney Museum in New York host a retrospective for him.

Weiner was someone from good America, someone the world listened to

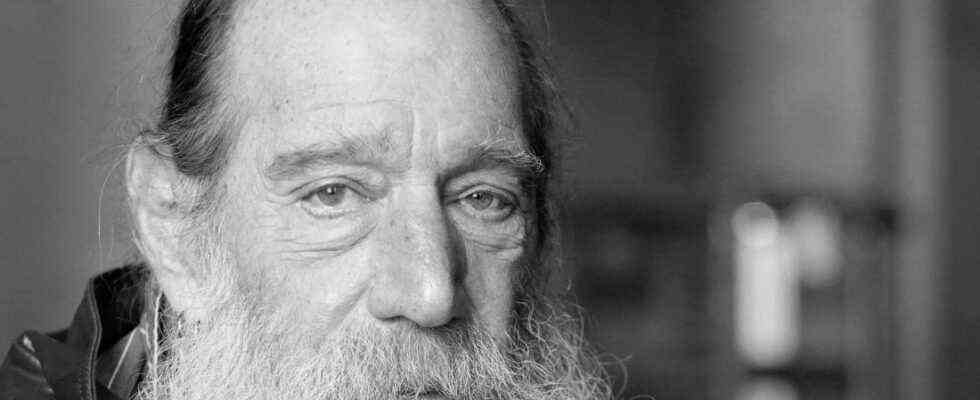

He then commuted between the USA and Europe and – as a lanky, tall man with a long beard and pigtail – ultimately even became an unmistakably prominent figure on the international scene who valued him as extraordinarily present and affectionate. As one of the most important living artists, he even humbly ennobled music videos, for example when Kanye West used a gallery in Soho as a backdrop. He sat there as an extra, in jeans and a flannel shirt. Weiner was someone from good America, someone the world listened to, like Bob Dylan or Patti Smith, just more eloquent and not a bit sentimental. He could even pronounce the sentence “I am an old tile” in the Rhenish accent.

Instead of in the end getting intoxicated by his own success, Weiner reflected awakely on how the scene had changed. Also because art was always a social concern for him, it was never about simply “setting up a new department” for art history: “After the Second World War we wanted everything to be popular. Now we have to see that the popular is not The solution is. Turning museums into fun is not the answer. Art is not the cause of the problem, but there has to be better answers. “

At one of his last major vernissages in Europe at the Kunsthaus Bregenz “WHEREWITHAL | WAS ES NEED” in autumn 2016, he was seriously ill with cancer. At that time he laconically stated that it was slowly becoming difficult for him. By which he meant neither working on the exhibition, appearing in front of the press nor speaking – but “my optimism”. Why? “Because he’s important. Even because of the younger ones. Give them a chance.” Who will remind the art world now, after his death?