Jimbocho is a small district between office towers and the city highway, which is also called “Hon-no-machi”, “book town”. Nowhere else in the world are there as many bookshops in such a small area as here, mostly antiquarian bookshops. They have more than ten million old titles in stock. Tokyo has been a book metropolis since the 17th century.

Today, 99 percent of Japanese are cut off from the literary heritage that resides in these stores and archives. They buy old books but cannot read them. The texts are written and printed in Kuzushiji, a script that the Ministry of Education abolished in 1900. It was created by vigorously writing with a brush, as a kurrent or “running text”, as it used to be called in German. Kuzushiji translates to “collapsed characters”. About 3.5 million books and documents in Kuzushiji have never been translated into modern Japanese. Even most historians cannot or only with difficulty read these texts. The Thai literary scholar Tarin Clanuwat has calculated that it would take more than a century to decipher and transcribe it if the few remaining Kuzushiji experts got together.

At some point she had an idea, she says. “How much faster would that be if the computer rewrote the texts?”

The writing system imported from China is actually not suitable for Japanese

Clanuwat has also been programming since she was young and wanted to try “artificial intelligence” – the computer should teach itself how to read Kuzushiji. Together with a team at Japan’s national institute for computer science, she developed an algorithm: “KuroNet”. Even in early versions, the program correctly recognized around 90 percent of the characters in simpler texts. A solid value, because until recently, teaching Kuzushiji to a computer was considered impossible. Artificial intelligences look for patterns and regularities. However, the Kuzushiji writers reduced their characters individually, everyone differently. In addition, there are hundreds or thousands of different characters in texts.

The root of the problem is that the writing system imported from China is not actually suitable for Japanese. In the first centuries after Japan adopted the Chinese characters, it didn’t matter. The few people who wrote did so in Chinese. It was, so to speak, Japan’s written language. It became more difficult when the Japanese began to write Japanese using the Chinese script in the 8th century.

The words of the basic Chinese vocabulary consist of a single syllable, Chinese does not conjugate or decline. Therefore, it is good to write with ideographic characters – graphic symbols that represent an object or concept. Japanese words, on the other hand, are mostly polysyllabic, Japanese not only conjugates verbs, it even puts adjectives in the past. For this, his writing needs grammatical elements. The Chinese writing system offers no solution for this.

In the 8th century, the Japanese began writing Japanese using the Chinese script.

(Photo: Imago/piemags)

So the Japanese started reducing some Chinese characters to a phonetic value. At the same time, they radically simplified these signs. This is how the Japanese syllabary alphabets came about, although they were never standardized until 1900. Everyone wrote their syllable signs as they wished. Some spellings prevailed, others disappeared again. The documents written in Kuzushiji testify to this proliferation.

The Kuzushiji scrolling text is extremely varied and therefore difficult to decipher.

(Photo: 17eme siecle/Imago Images/Kharbine-Tapabor)

For centuries, only men wrote in kanji, the characters adopted from China, to demonstrate their classical education and superiority. It was said that the women were uneducated, they used the characters reduced to phonetic syllables and “collapsed” in the sweeping handwriting because they had not learned any kanji. Which in some cases wasn’t true. But the kanji were reserved for men.

“In the 14th century, a court poet defined three categories,” said Clanuwat: “He compared correctly written kanji to a standing person, loosely written ones to a walking person. He said the kuzushiji kanji were running.”

The AI programmers don’t know Japanese, but they translate old Japanese texts

KuroNet is now freely accessible online, but only in Japanese. The system needs about two seconds per character. To improve it, three years ago Clanuwat’s institute announced a competition for self-learning Kuzushiji reading programs on Kaggle, a platform on which companies and institutes publish software problems. Cash prizes totaling $15,000 were up for grabs. 293 teams took part.

The second prize was taken by Konstantin Lopuhin from Moscow, a deep learning specialized software developer. He had previously evaluated satellite images with artificial intelligence and categorized sea lions. In the Skype interview, Lopuhin does not speak of kanji or characters, but of “objects” and “classes”. Is there a difference if the computer has to recognize characters instead of sea lions? “Yeah,” says Lopuhin, “there were five classes for the sea lions, and about twenty for the satellite images. But for the Kuzushiji, there were more than 4,000. Also, I don’t speak Japanese, I couldn’t even spot obvious mistakes.”

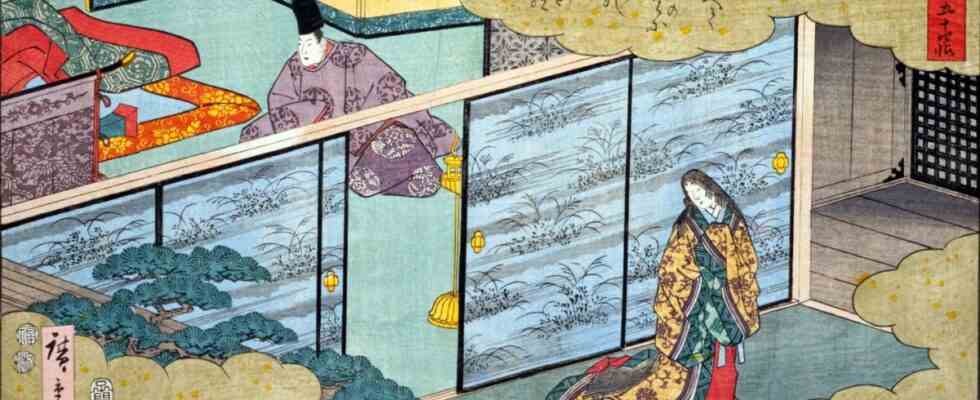

To this day, Lopuhin does not know what is in the texts that his program has deciphered. A third of the 45 texts to be deciphered for the competition were cookbooks, plus a book from 1639 on Christianity, one on silkworm breeding and a lot of literature. Including a copy of the first chapter of the “Genji”, which is considered the Japanese book of books and the first novel in literary history. The lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu wrote the story of a prince’s love adventures in the first decade of the last millennium – a time when people met to read their poems of cherry blossoms, autumn leaves, mist and the moon, of love and their impermanence. They drank rice wine and had affairs. Love was free, at least for men. After all, the women had their own thickets of signs. They wrote Kuzushiji – peppy, “running”.

Can one expect the discovery of unknown masterpieces when the computers en masse transcribe Kuzushiji texts? “I don’t think so,” says Clanuwat. “But you will find explanations of old terms that we have not yet understood exactly. Small puzzle pieces with which everything suddenly makes sense.”