It is a striking decision when an author lets the heroine of his novel die after little more than fifty pages. So it is with Elizabeth Finch. The English writer Julian Barnes, who invented them, has a justifiable reputation for knowing exactly what he is doing in his narrative maneuvers. He didn’t tear the university lecturer out of her life, she had long since retired when she quickly succumbed to an illness.

Decades ago, one of her seminars for adults on “Culture and Civilization” was attended by the novel’s first-person narrator, Neil, a former actor and screenwriter who, after ending his career as a supporting actor in TV series, later switched to the restaurant industry polished classic cars and occasionally looks back on his two failed marriages.

From the beginning he tells of a dead woman, everything we know about Elizabeth Finch we owe to him, for example that she was a recreational smoker and dressed very conventionally (“In the summer a skirt with a box pleat, usually navy blue, in the winter tweed”), but also the titles of the two books in her narrow list of publications: “explosive women about London anarchists between 1890 and 1910 and Our Necessary Myths about nationalism, religion and family.”

Finch subjects all monocultures, including monogamy and monotheism, to a scathing critique

Not writing books is at the center of her intellectual existence, but oral teaching (“She stood before us without notes”), which En passant-Production of aphoristically pointed sentences, the dialogue with their listeners. She quotes the Stoic philosopher Epictetus and has a decidedly critical attitude towards the English nation and towards Christianity.

She puts the stories of saints in the medieval “Legenda Aurea” in the acid bath of historical and source-critical skepticism. On the subject of “Slavery and its Abolition” she clarifies “that the British kept slaves on the American continent almost twice as long as the Americans”, the leitmotif of their teaching is the warning against the prefix “Mono”. At best, she accepts monographs. She subjects all monocultures, including prescribed monogamy, but above all monotheism, to devastating criticism.

This teacher of a type he didn’t know when he was at school kept Neil spellbound beyond seminary, seeing her two or three times a year until her death. In her will she left him all her papers and her library. He reads her notes, considers a publication, considers writing a biographical portrait of her. One of his daughters once called Neil the “king of unfinished projects”. As far as the biography is concerned, she will be right.

Julian Barnes: Elizabeth Finch. Translated by Gertraude Krueger. Kiepenheuer & Witsch 2022. 240 pages. 24 euros.

(Photo: Kiepenheuer & Witsch/Kiepenheuer & Witsch)

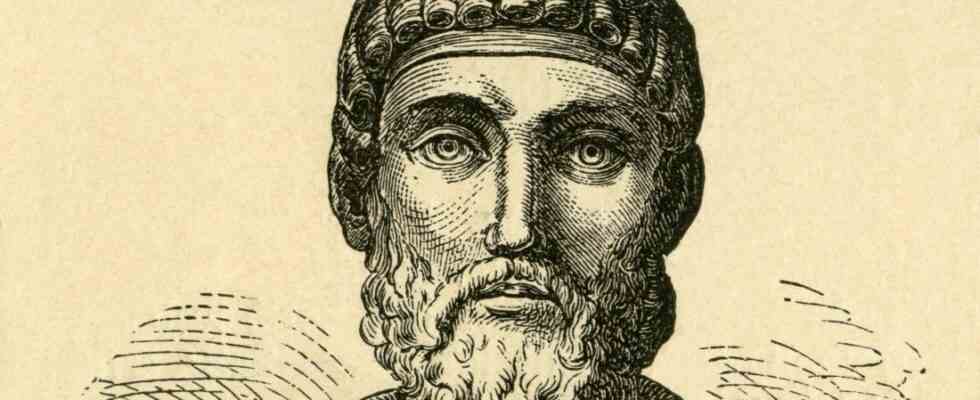

But Neil found in Elizabeth Finch’s notes a figure who already played a key role in her seminar: the Roman emperor Flavius Claudius Julianus (331 – 363), “Julian Apostata”, who apostatized from Christianity and declared war on him, not had less in mind than to undo the Constantine revolution and rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem, but who combined his sharp criticism of Christianity with tolerance towards Christians instead of a new persecution of Christians. Julian Barnes fills the second part of his novel with the essay that Neil writes about Julian Apostata, because he read this commission from the estate of the revered teacher.

From the beginning, Julian Barnes’ work has included essays on past and present literature, the bibliomania of his early years, important colleagues like Penelope Fitzgerald or Anita Brookner or his experiences with the visual arts. He dedicated an entire book, “Nothing to fear” (2008, German 2010) to the question of the appearance of his own death in life and in it he tells a great deal about his own biography. Reflections, essayistic digressions add to the appeal of his novels.

Elizabeth Finch came from this source of energy in his writing. She may have been an elderly lady when she died. In her author’s work she was a very young character. By her death after just fifty pages, Barnes has opted out of the option of developing her into a British counterpart of Australian writer Elizabeth Costello, who is the South African-born, long-time Australian resident author John M. Coetzee, winner of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Literature Invented at the end of the last century and made into a figure of intellectual challenge and aggravation in a series of essayistic tales, scandalous speeches about animal testing and the Holocaust, secular modernity and the post-colonial age, and last but not least, reflection on literature.

Neil is one of the many aging men who look back on their lives in Barnes’s novels

The consequence of Elizabeth Finch’s early death is that it is not her voice but that of her student Neil that dominates Julian Barnes’ novel. This gives him the character of a necrologist who is happy to fulfill the commandment to say only good things about the dead. Now, Barnes wouldn’t be Barnes if that were all. He has made Neil a revenant of the many aging men who in his novels look back on their lives with few truths and many lies.

One of them is Adrian Finn, the first-person narrator in the Booker Prize-winning novel The End of a Story. In the Barnes cosmos, these aging men have a duty to mediocrity. Her author tries to compensate for her mediocrity by suggesting an artfully hinted reverse side of her existence, in which it descends steeply into veritable abysses.

In this novel, that succeeds only to a limited extent. Neil loosens up his Julian Apostata essay, which wafts through the aroma of excerpts from encyclopedias and biographies, with occasional flippant remarks. But that’s it. In Elizabeth Finch’s older brother, he meets someone who experienced her energetic intelligence rather painfully, but there is no dark counter-track between the lines either.

The secular saint legend of Elizabeth Finch lacks monstrous features

Neil’s relentless attempts to apprehend a lover of his idol haunted by her brother’s memories reveal that his interest in Elizabeth Finch is not balanced by his awe at her brilliance. “I would like to argue that failure can teach us more than success and that a bad loser teaches us more than a good one,” the lecturer teaches. Neil retrieves this insight, which has spread to modern management courses, as proof of its originality. The secular legend of the saints he writes lacks monstrous features.

He looks back on an affair with a fellow student in Finch class and tries irresolutely to reactivate her in the third part of the novel. But that flutters like the portraits of the other fellow students. Early on, in a seminar session on Hitler and World War II, Barnes raises the question of whether Elizabeth Finch might be of Jewish descent. In the third part, in which Neil continues his biographical research after his apostata essay, it is taken up, but remains a narrative dud. It is no different with the scandal that Elizabeth Finch gets caught up in when the tabloid press pillories her criticism of Christianity during a summer slump. Neil accesses this episode primarily to give his heroine some kind of martyr status. In the end she emerges as a precursor to contemporary self-criticism in post-colonial and post-Brexit England.

In his last novel “The Man in the Red Coat” Julian Barnes unfolded a kaleidoscope of obsessions regarding the personalities of the aesthetic and scientific avant-garde in England and France in the late 19th century, without ignoring the borders between “fiction” and ” Non-Fiction” still respected the laws of literary realism. In contrast, this novel has something unfulfilled, unexploited. It is not due to the basic idea of letting thoughts, theories and beliefs gain figurative existence. It is due to the disproportion between the design of the titular heroine and the narrative conventionality of her student and necrologist Neil, whom Julian Barnes allowed too little ambiguity.

Julian Barnes: Elizabeth Finch. Novel. Translated from the English by Gertraude Krueger. Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag, Cologne 2022. 240 pages, 24 euros.