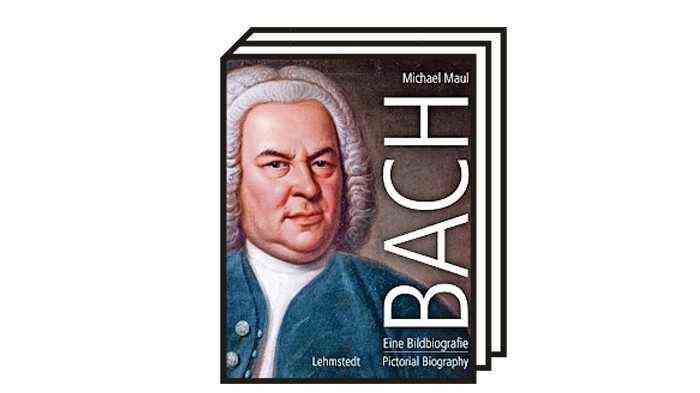

For many, he’s a bit like Jesus. The closer you get to Christmas, the closer you feel connected to it. Johann Sebastian Bach, venerated as the “fifth evangelist” by early biographers, is a fixed point in music history not only for the numerous lovers of his Christmas oratorio, but also for all subsequent musicians, especially composers. With more than 1000 works, including summit works such as “The Art of Fugue”, Bach provided templates for compositional and musicological discourses over the centuries. The Leipzig Bach researcher Michael Maul shows this in his opulent Bach picture biography (Lehmstedt Verlag, Leipzig. 312 pp., 30 euros), which is partly based on his audio biography “Universum JSB” in Deutschlandradio Kultur, to listen to in 33 episodes jsbach.de. With regard to the Christmas Oratorio, he naturally refers to Bach’s own compositional models, all of which are secular works, which he has now put together into an opus magnum with new texts, additional recitatives and chorales. But, says Maul, “if we didn’t know about this prehistory, we would never suspect that the immortal sounds of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio had a secular prehistory”. This touches the core of Bach’s musical language, which is so clearly ambiguous that it speaks to us particularly clearly when we cannot say what its meaning is.

Of course, natural and correct: Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio BWV 248 by the singing group “Ensemble Polyharmonique”.

Just in time for the festival, the singing group “Ensemble Polyharmonique” accompanied by Thuringian Bach Collegium, presented a new recording of this Bach hit (Rondeau). It sounds so natural and correct that the usual questions about the original sound and authentic instrumentation rarely arise. What was still a decisive criterion and sometimes also a problem in the reference recordings of the past – from Gerhard Schmidt-Gaden to Nikolas Harnoncourt – has become a matter of course in music. Conductor Gernot Süßmuth immediately finds the right tempo and a pleasant narrative tone.

On the other hand, Johann Sebastian Bach’s piano music has recently flourished again. Not just the superstars of the scene, for example Long long with the Goldberg Variations (Sony) or Daniil Trifonov with the “Art of Fugue” (DG) are dedicated to the forefather of modern European music, but also to the French keyboard star David Fray (Erato), the Italian Filippo Gorini (alpha) and a number of lesser-known pianists. Especially among the latter are pioneers of Bach reception, for example with Wanda Landowska in the first half of the 20th century.

The French harpsichordist Blandine Verlet.

Some have been forgotten, such as the French harpsichordist Blandine Verlet, to which an edition is now dedicated (Decca). Not with works by Francois Couperin, with whom she became known, but with compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach. Verlet is a natural harpsichord player, not a disguised pianist who swaps one instrument for another out of historical fashion. Which would not be reprehensible, because in Bach’s time it was basically irrelevant which keyboard one operated in order to be considered a piano player. What makes Verlet exciting even today is her game, which seems very subjective, but also the material technical requirements; the great replicas of historical instruments that convince and fascinate right from the start. She plays Bach’s Goldberg Variations on a harpsichord from 1730 by Nicolas du François Blanchet, which was recreated by William Dowd in 1976. This is a delicate undertaking, a science in itself, and by no means always works satisfactorily. But it means a lot for the presentation of early music. The individual voices automatically sound more equal here because they cannot be weighted differently to the extent that it is possible on a modern grand piano and is always the case in reality.

Lost in a dream: David Frays Goldberg Variations by Bach.

(Photo: Erato)

What at David Fray emerges abundantly. He opens the Goldberg Variations in a very unbachish way, lost in dreams. Topic missed? Yes, but his variations on the theme occasionally unfold that genuine musical power that is not achieved through increased sensitivity, but through maximum concentration on the constructive essentials and their tonal realization.