To understand why Art Blakey’s January 1961 tour of Japan was such an important step in his life, one has to go back briefly to his childhood and youth. He wasn’t originally a drummer, but a pianist. And playing the piano wasn’t a vocation either, but first of all a way out of the agony of child labor in the coal mines of the Appalachian Mountains in southwestern Pennsylvania. Blakey was orphaned by a foster mother in Pittsburgh. Shortly after his tenth birthday in October 1929, the Great Depression began with “Black Thursday”. You didn’t ask long whether you were old enough to work.

Blakey’s biography has never been clearly documented, but it is considered relatively certain that by seventh grade he was good enough at the piano to earn enough money in the bars of the steel and coal city that he no longer had to go into the mines . But one night in the early 1930s at the Democratic Club, an after-hours joint in the Shadyside entertainment district, the gangster who owns the place was so smitten with the young pianist Erroll Garnerthat he ordered Blakey from the piano to the drums with his gun drawn. According to legend, Blakey found his feet surprisingly quickly and was soon working as a drummer for pianist Mary Lou Williams and in the orchestras of Fletcher Henderson and Billy Eckstein.

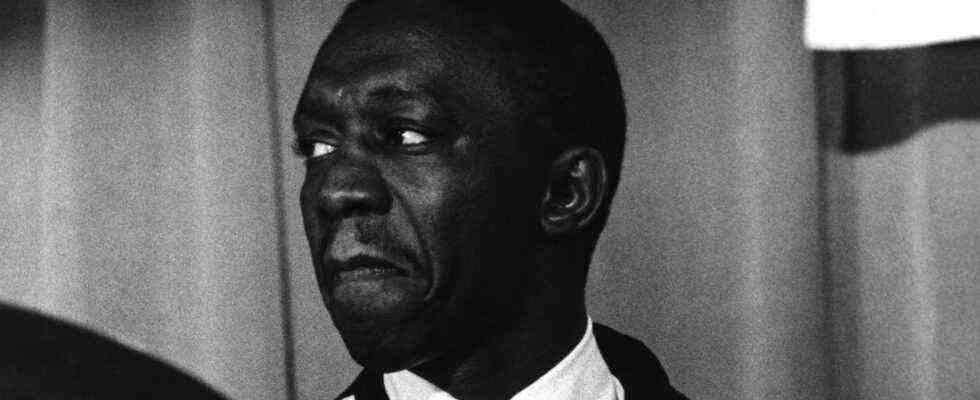

First Flight to Tokyo

(Photo: Blue Note)

Right at the beginning of the recording from the Hibiya Public Hall in Tokyo (which has just been reissued as a magnificently designed double LP and also in all other formats under the title “First Flight to Tokyo”) you can already hear in the drama of the first double hit powerful crash cymbals that Blakey was well aware of the magnitude of the moment. The five African American musicians performed in a classical concert hall. Not in any. In the first classical concert hall that was built after the end of the war in the country of the nation that fifteen years earlier had been an opponent of the war and the target of the two American nuclear attacks.

Respect!

Right on arrival, Wayne Shorter recalled in a recent one Conversation with label boss Don Was, they were overwhelmed by the enthusiasm and respect with which they were greeted by a crowd at the airport. Two Hollywood stars had been on board, Shirley MacLaine and Edward G. Robinson. But most of the thousands of fans came for Art Blakey and his Jazz Messengers. “We knew we were valued there in a way we’d never felt in America.”

Shorter was the tenor saxophonist at the time. Trumpeter Lee Morgan had brought him into the band almost two years earlier. Morgan was 22, Shorter just five years older. Both had completed their big band apprenticeships and were ready to become stars in Art Blakey’s talent factory. The fire with which Morgan plays at this concert and the blazing strength with which Shorter supports him shows very clearly why both became titans. But pianist Bobby Timmons and bassist Jymie Merritt also give their all.

Star among stars

But Blakey had the most astonishing top form that evening. Otherwise he rarely played solos. He ran his Messengers as a collective, often opening tracks with the addition “featuring nobody” to make it clear that everyone on stage was a star, not just him. This was underpinned by his drumming style, which is perhaps the most recognizable in jazz history. He didn’t fill breaks and bridges with the usual arabesques on toms and cymbals, but with press rolls that, strictly speaking, anticipated the snare drum crescendos with which house music has many would produce ecstasy years later. Cymbals were not accent points for him. He is said to have been the first to hang a key chain on the ride cymbal, creating a wall of sound that turned the swing into a storm swell that propelled the rest of the band in not-so-gentle waves. In Tokyo, however, he kept playing solos. Mighty drum symphonies. A rare opportunity to hear in its purest form the polyrhythms he brought back from his years in Africa.

“Last Flight to Tokyo” is just one of the many Art Blakey albums currently being reissued by Blue Note. There are few label bosses who devote as much passion and precision to the care of their catalog as Don Was has done since he took over Blue Note almost ten years ago. The most important phases of the Jazz Messengers can now be called up again. The hit albums they recorded with Lee Morgan like “Moanin'” and “The Big Beat”. A rarity from the early days when Clifford Brown and Lou Donaldson provided horns for “A Night at Birdland” and Horace Silver played piano. Or the later phase, when Freddie Hubbard was added as a trumpeter and Curtis Fuller enlarged the sound with his trombone – as on “Free for All” and “Mosaic”. Even a lost studio session, which saxophonist Hank Mobley messed up because he didn’t have his embouchure under control that day and kept squeaking away, has been released as “Just Coolin'” for the first time. And great despite the blunders.

just coolin’

(Photo: Blue Note)

What is particularly astonishing about Blakey’s Blue Note records is how low the entry threshold for modern jazz was. He not only hired virtuosos with team spirit, but also people who could write. The hits of his protégés like “Dat Dere”, “Along Came Betty” or “Blues March” ran as singles in jukeboxes back in the late fifties and early sixties. You only have to listen once and understand it immediately. The pressure on the dance floor that Blakey produced on drums hadn’t been seen since the swing days. And with the power of modernity. The series of new editions should actually be given the title “Welcome to the Thunderdome”. With the note that there are no losers here.

A playlist with excerpts from the albums discussed and some more from Art Blakey can be found on Spotify here.