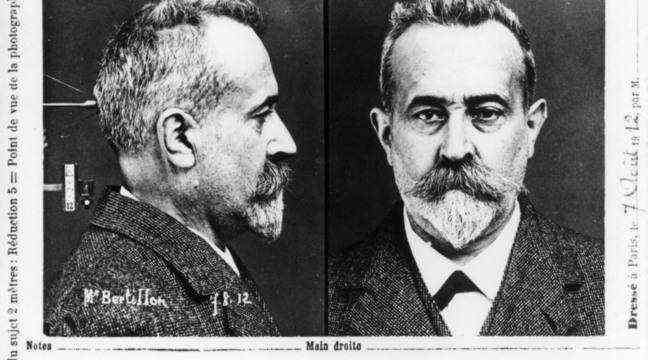

Paris, October 16, 1902. In his office in rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, dentist Auguste Alaux discovers, in the early morning, the lifeless body of his servant. Joseph Reibel, 45, was murdered and theft appears to be the motive for the crime. In the absence of witnesses, the investigation promises to be difficult. The Commissioner Prélat des Champs-Élysées, and his secretary, Inspector Magnan, go there, and find that valuables have disappeared. A locket lock, which contained hundreds of coins, was torn off. The examining magistrate Jolliot then asks, Alphonse Bertillon, to go to the scene. He relies on the expert eye of the director of the Forensic Identity service to find clues that investigators lack.

Immediately, Bertillon’s attention is focused on the windows of the fractured medal-holder. On the broken pieces, he isolates four fingerprints that he takes to the anthropometry department for analysis. First observation: they do not belong to the victim. He will then compare them with the hundreds of others contained in his file, made up of cardboard cards. On one of them, the prints seem to match perfectly. The file is in the name of a certain Henri-Léon Scheffer, who had been arrested on March 9, 1902 for theft and breach of trust. The investigators were interested precisely in this man who knew the victim. He informed the judge of his conclusions in a report dated October 24, 1902. Six days later, the suspect was arrested in Marseille and confessed.

An outdated classification system

Bertillon thus becomes one of the first police officers to discover the identity of a criminal thanks to the examination of his fingerprints. However, the criminologist, born in Paris on April 22, 1853, has long been reluctant to add these traces to his data sheets. “Initially, he was not necessarily a supporter of this method, which came mainly from England. But as it was used in other countries, he ended up realizing that it was essential, ”explains Christophe Soullez, police specialist and co-author of the book. 3 minutes to understand the 50 greatest criminal stories in our history*.

Alphonse Bertillon, Favre. Sebastien. 36 years old, born in St Étienne (Loire). Trader. Carrying a prohibited weapon, anarchist. 2/20/94., 1894 https://t.co/fWGij0IjF3 #photography #themet pic.twitter.com/0r9FW4BLNs

– The MET: Photography (Bot) (@met_photos) August 5, 2021

Bertillon was convinced of the superiority of the anthropometric method that he had put in place after being hired at the police headquarters (thanks to his father) as a clerk in writing, in 1879. In the attic, he was responsible for classifying the files which contain information on the people who have been arrested by the Parisian police. But he soon realizes that the classification system used is outdated and impractical. It is almost impossible, among these millions of records, to find that of a particular individual.

“He also sees that offenders have understood the system well and give false identities when arrested. However, at the time, one of the main concerns of the public authorities was to fight against repeat offenders. However, the system did not allow them to be confused, ”continues Christophe Soullez.

“He took a considerable step forward for the judicial police”

He will then design a system based on nine anthropometric measurements: the Bertillonage. Concretely, it measures different parts of a person’s body with a caliper and cephalic forceps and notes the data on a card. Size, wingspan, body length, trunk, right ear, left foot … No chance that we find these measurements in someone else.

The prefect of police, Louis Andrieux, takes Bertillon for a madman and does not want to hear about this method. His successor, Ernest Camescasse, is more open and will give him three months to test his method. Bertillon will then measure all the defendants brought to the depot. And the results are not long in coming. Of the 19,771 individuals passed through his hands, 290 are identified as repeat offenders, notes the book At the origins of forensic science, Alphonse Bertillon, precursor of the science of crime. His method allowed the arrest in March 1892 of the anarchist Ravachol, who had been “bertillonné” in the prison of Saint-Étienne two years earlier.

In 1893, at the instigation of Prefect Lépine, the identity office, created ten years earlier, merged with the photographic service and that of judicial springs. The forensic identity service was born. 128 years later, it still exists. “When serious crimes are committed, the forensic identification services move to take traces and clues, freeze the crime scene. They will then classify, analyze, interpret all these elements, ”emphasizes Christophe Soullez.

Bertillonage, which was adopted by many police forces in Europe, was used in France until 1970, before being permanently replaced by fingerprint analysis. But the work of Bertillon, which died out in 1914, propelled the police into a new era. Police can now prove a suspect’s involvement in a case, even without a confession on his part. “He has taken a considerable step forward for the judicial police,” concludes Christophe Soullez.

* 3 minutes to understand the 50 greatest criminal stories in our history, by Christophe Soullez and Alain Bauer, Le Courrier du Livre editions, 160 pages, 19.90 euros