When Viktor Ullmann conceived his opera “The Fall of the Antichrist” in 1935, which is now being shown at the Leipzig Opera in a successful new production by Balázs Kovalik, he could only guess how bad everything would be in Europe. Nevertheless, he found the courage of the desperate to continue to hope that in the end everything would be in God’s righteous hands and that it would not come to the extreme. But it did. As a baptized Jew, Ullmann was initially deported to Theresienstadt and then gassed in Auschwitz. Perhaps that is why one encounters his works with an anxiety, as if performing them were a compulsory exercise, an act of atonement that had to be dutifully performed.

Ullmann has his very own sound language, difficult, catchy, painting

But with which one would do a great injustice to this work. Because it is artistically at the highest level, in terms of form and content, and does not require any political justification. The second serious injustice that put an end to the music from the 1920s and 1930s after the war was the one-sided focus on an avant-garde claim in the tradition of Arnold Schönberg, i.e. serial music. The philosopher Theodor W. Adorno did a great job here, composers like Paul Hindemith, especially the offshoots of the New German School, but also all those who pursued a so-called moderate modernity like Viktor Ullmann does so virtuously, were and are in the bubble of the New music apologists as inferior, at least as reactionary.

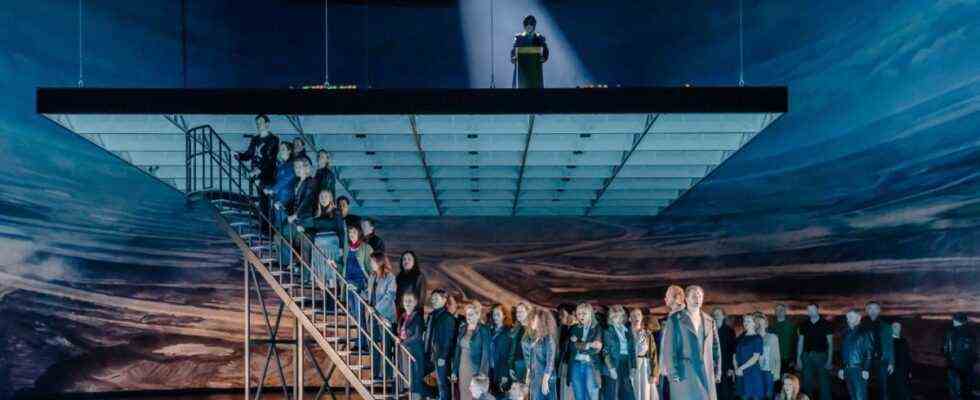

In any case, it is not consistently disturbing, destroys sound, and changes listening habits every minute. Ullmann has his very own sound language, fantastically difficult, at the same time wonderfully catchy and imaginative, which he develops confidently without having to permanently distance himself from others. You are allowed to listen to other music, also to establish concrete references – Ullmann’s music can withstand that without getting lost in arbitrariness or eclecticism. And so this horror opera begins in a soft string minor. Under a floating pedestal, perplexed humanity waits for redemption, above, also somewhat uncertain, the three protagonists – poet, priest, technician – to stand up to the power-hungry regent, who is increasingly mutating into an angry dictator. In the end, it will be the poet alone who shows the backbone and ends up in dungeon. The engineer who is supposed to prepare the space flight gets cold feet, the priest reluctantly comes to terms.

From the orchestra pit, which the conductor Matthias Foremny and the Gewandhausorchester have mastered just as confidently as the brave ensemble of singers on stage, clarinets sound like big question marks, stubborn bassoons counter it, muted brass players have minor objections here and there. The crucial question is whether it will be possible to unite against the dictator. “If we do not overcome the opposites, we will fall prey to the usurper,” shouts the priest. The final roll call to the audience – “Don’t split up!” – shows that Ullmann is serious about this thesis. But one could also think the opposite: only a united people is suitable for a dictatorship, which is why every dictator is busy from morning to night and with all means to establish this state of unity. It’s always about a new spirit that should blow everything through with a fresh political wind.

So here too, where the dictator demands propagandistic aid from the poet. Humanity has changed, needs a new language: “You are called”, and when he refuses: “You stay in prison.” The tone in the orchestra is now also sharper, the trumpets shedding their soft mutes. “If you want to be a god,” the dictator throws at the poet, “don’t resist evil. Suffer! Suffering releases you”. The music becomes more complex, evil creates space, and Mahler’s sounds of desperation creep in.

Ullmann felt so firmly rooted in Austria that he no longer fled in time and was murdered in Auschwitz in 1944

The fact that too many topics have to be dealt with in parallel in the stage action does not do the drama any good. When it comes to fundamental issues such as the continued existence of the human, the problem of too great a belief in technology is difficult to negotiate with the same intensity. There is already so much misbelief in the play – the defamation of space travel as an insane belief in miracles becomes secondary. Especially since humans actually flew into space 30 years later.

In 1935, just two years after Hitler came to power, with the passing of the Nuremberg Race Laws, the situation had become life-threatening for baptized Jews like the Ullmann family. Ullmann’s parents had been baptized as Catholics, the father was a colonel in the German Army and was even raised to the nobility. Viktor Ullmann also volunteered for military service, studying law at the same time, and finally music. None of that mattered anymore. Nevertheless, Viktor Ullmann felt so firmly rooted in Austria that he no longer fled in time and was murdered in Auschwitz in 1944. In this crucial year of 1935, Ullmann set out in what was supposedly still safe Vienna to bring the political situation into an artistic state that one could deal with, that one could control. “The fall of the Antichrist” was created based on a text by the Swiss anthroposophist and Rudolf Steiner successor Albert Steffen. You can see that in the opera, the sun and planets are part of the action, the whole cosmos that the hybrid dictator wants to conquer by means of space travel.

Connected with this, of course, are Christian symbolism and mysticism. The admirers of the great teacher and the longing for divine worlds. “I am human and may be with gods,” the poet cheers quietly, and in quiet euphoria: “The gods take me into their midst.” In the orchestra allusions to Wagner’s “Götterdämmerung” are increasing; the gods may no longer be able to keep what man makes promises. The harmonies break away from their task of grounding and anchoring, they remain open, float, and relatively restrained trumpets no longer paint just traditionally hell, but the whole cosmos.

As if the music foresaw what the mild, peaceful end of the opera is not yet willing to admit

The dictator, too, likes to move in the orbit of benevolent esotericism and newly awakened Christian faith, as expected, he escalates into a narcissistic megalomania: “I am the savior, not Christ!” And when he had bread distributed to the masses – “synthetically made of stone” – the poet spoke meaningfully: “You eat his spirit.” And it becomes even clearer: the bread is poisoned. The priest knows it and still sacrifices himself as a taster, then falls into animal madness. “Because he mocked me,” shouts the dictator. But by then it is already too late, the people no longer trust him, preferring to turn back to “Christ Jesus”, as he is called throughout this opera. And because the orchestra repeatedly falls into the sound of Wagnerian worlds, this opera has also been called “Ullmanns Parsifal”. However, this reflex disavows both works equally. Ullmann does not copy Wagner’s sound ideas either, he does not even quote them where one might suspect a Tristan appeal and an immersion in the “Götterdämmerung”. That can resonate, that is definitely a signal, but more in the sense of a cross-reference from a great temporal and aesthetic distance.

In the end it becomes abundantly clear when suddenly the Brechtian theater concept rumbles in. “The fall of the Antichrist,” shout poets and resurrected technicians, and then at the end of the picture a large red banner appears with the slogan: “Do not part.” In addition, the orchestra really gets going, escalates to an apocalyptic riot of wind instruments, spurred on by the beating of the drums to a total sound that promises a terrible end. As if the music foresaw what the mild, peaceful end of the opera is not yet willing to admit. In his so far best-known opera “The Emperor of Atlantis or Die Tod-Denier” – composed in 1944 and premiered in Amsterdam in 1975 and in the most original possible version in Berlin in 1989 – Ullmann then becomes more concrete, no longer trusts mysticism and draws from its painful life Experience a deeply Christian conclusion: that one can counteract the tyranny of evil, including tyranny itself, only through sheer humanity. This idea has since gone a little out of fashion, but its truth – whether mystically embellished or ideologically concretized – is timelessly valid in Ullmann’s operatic art. Great cheers in Leipzig.