Exclusive

As of: 03/10/2023 6:01 p.m

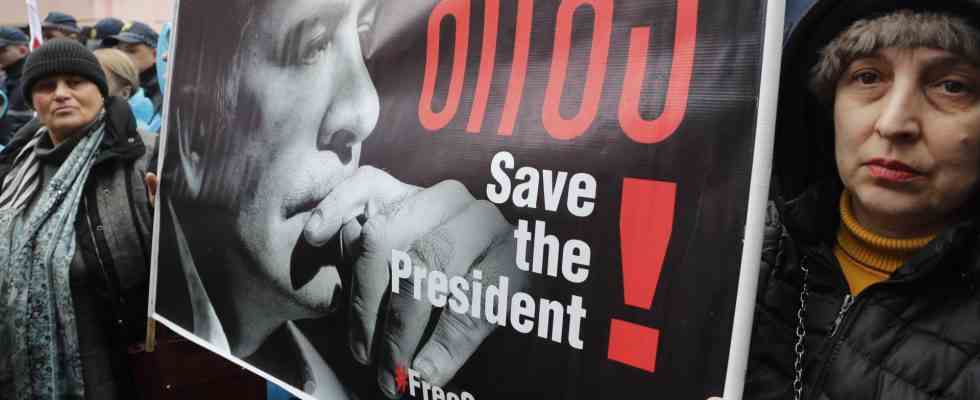

The government in Georgia shows no mercy towards the imprisoned ex-president Saakashvili, who is in poor health. Eyewitness testimony suggests how far the government may go.

Protesting against the rulers is part of the culture in Georgia. One prominent figure was missing from the current uproar against the law on “agents of foreign influence”: Mikhail Saakashvili. The former president of Georgia himself once provoked massive protests and used violence to put down demonstrations.

Saakashvili angered the people so much that in 2012 his United National Movement party lost to the new Georgian Dream party – led by very wealthy businessman Bidzina Ivanishvili. He had secretly supported Saakashvili’s government for a long time. Over the years, his sympathy turned into rejection and finally personal enmity, which he does not hide in his statements about his political opponent.

After being voted out of office, Saakashvili was sentenced to six years in prison for abuse of power. He escaped imprisonment and went to Ukraine, where he became governor of the Odessa region – and yet he couldn’t let go of politics in Georgia. He repeatedly announced his return and the expulsion of Ivanishvili’s party from power until he returned secretly in autumn 2021, but was caught by the police a few days later and ended up in prison.

Poisoned in prison?

Many in Georgia saw his sentence as justified and when he went on hunger strike and denounced ill-treatment, it was excessive. Finally, his lawyers and experts claimed that Saakashvili was poisoned with heavy metals. He had to be taken abroad for treatment. In fact, in December at a court hearing, to which he was connected via video from the hospital, he only looked like a shadow of himself. The 55-year-old was emaciated and gray, and had visibly deteriorated physically and mentally.

Despite urgent appeals from home and abroad, the Tbilisi City Court has so far refused to suspend the sentence – the judiciary in Georgia is considered politically dependent. The government is unyielding. During a panel discussion at the security conference in Munich, Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili impassively accused Saakashvili of only faking his decline and of being to blame for his condition.

How far does the enmity go?

Garibashvili was once Ivanishvili’s assistant. Other former employees and loyalists of the businessman who once made his fortune in Russia also hold important posts in the country. The question is: what would Ivanishvili and his people put up with and how far are they willing to go – against Saakashvili and people associated with him?

A young man who at first glance has nothing to do with Saakashvili asks himself this question: a 32-year-old Chechen. Issa is his name here, but he doesn’t want to give his real name publicly out of fear for himself and his family. His story cannot be examined in detail without endangering himself and others, but it is plausible.

Issa grew up in Georgia’s Pankisi Valley and Chechnya. The Chechen wars in Russia shaped his childhood. He knew former fighters – including Selimchan Changoschvili, who was murdered by a Russian in Berlin’s Tiergarten in 2019. The order came from the highest authorities in Moscow, as the Berlin Court of Appeal determined in its 2021 judgment.

Khangoshvili fled to Germany in fear for his life after surviving an attack in Tbilisi in 2015. However, the Georgian authorities did nothing to clarify the case or otherwise protect Khangoshvili. He and other Chechens are opponents of the ruling party because they once cooperated with Saakashvili’s leadership. She also avoids any conflict with Russia.

After the attack, Changoshvili hoped for Saakashvili’s support and followed him to Odessa. He hired young Issa as a bodyguard. But after a few months they left the Ukraine because the situation there was becoming too insecure. In 2017, a former comrade-in-arms of Khangoshvili was killed in a car bomb attack in central Kiev.

Statements on Saakashvili demanded

Issa’s death haunts Changoshvili to this day: When he entered Georgia in May 2022, he was questioned three times – right at the airport, then one day and again two weeks later in a police station in the Pankisi Valley.

The employees of the State Security Service of Georgia (SSSG) were first friendly and then increasingly aggressive, he reports. The SSSG is a broad-spectrum security agency reporting directly to the Prime Minister. Issa remembers three names: Morisi, Vano, and Dato.

They were apparently intent on extorting statements from him that lead to his connection to Khangoshvili and, via that, to Saakashvili: Issa was supposed to testify that it was Saakashvili’s United National Movement party that lured him back to Georgia in 2021 and ensured that that the police were able to execute the arrest warrant against Saakashvili. In addition, Issa was to explain that the party wanted Saakashvili dead and that it was to blame if Saakashvili died in custody.

What initially sounds far-fetched fits with statements by members of the government such as the one that Saakashvili is only faking his decline. And it would confirm their worst fears that they would accept the death of the former president – even as there are warnings from MEPs that Georgia will then not be granted candidate status later this year.

The Greens MEP, Viola von Cramon, says: “The political developments in Georgia are viewed very critically by a large majority here in the European Parliament.” All friends of Georgia are shocked that Saakashvili has neither been given a fair trial in Georgia nor has he been imprisoned under dignified conditions.

“But the fact that a debate about a humanitarian transfer to a hospital outside of Georgia is not even being considered and that the Georgian government is basically accepting a possible death of Saakashvili is another low point in cooperation with the EU . Should he actually die, the country’s EU prospects will probably be buried for the time being.”

fear of returning

After the third interrogation, Issa contacted a former confidant of Khangoshvili. He inaugurated a politician from the United National Movement, whose name is known to the author. The politician said that if Issa agreed to make these statements, he would be a risk to the Georgian government. He should better go abroad. Like many of Khangoshvili’s relatives, Issa also fears that he will not be safe from acts of revenge from Russia in Georgia. Relatives of opponents and former combatants have also been harassed, kidnapped and even killed for a long time.

Issa went to Germany and applied for asylum, which was rejected. The administrative court in Potsdam rejected an urgent application against the decision last week, also because Sweden had not granted him asylum. Issa also fears for his wife and four children, who live in a home and face deportation any day. “The authorities won’t believe us until we’re dead,” he says, referring to Changoschvili, who also wasn’t granted asylum in Germany because he wasn’t in any danger.

“Due to the delicate domestic political situation in Georgia, all authorities in Germany should examine a deportation very carefully and, in the best case, suspend this for the endangered applicants until further notice. On the other hand, the lives of those potentially to be deported cannot be guaranteed,” appealed the Greens politician from Cramon.