Dhe suspicion has existed for a long time: but now proven a large US study clearlythat the extremely widespread Epstein-Barr virus is the main cause of multiple sclerosis. An infection with the pathogen increases the risk of developing the autoimmune disease by a factor of about 32, the researchers report in the journal Science. This makes the virus by far the most important cause of the disease – and probably also a necessary prerequisite.

“This work is the last piece of the puzzle,” says Klemens Ruprecht, head of the multiple sclerosis outpatient clinic on the Mitte campus of the Berlin Charité. “The results leave practically no doubt about a causal connection.” However, it is also clear that the vast majority of infected people do not develop any multiple sclerosis.

Because around 95 percent of all people become infected with the to the in the course of their lives herpes viruses counting Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) – usually in childhood. The infection, which is usually transmitted via saliva, is usually asymptomatic, but can cause glandular fever in adolescents and adults – sometimes also called kissing disease or student fever because of the transmission route. The illness goes with it fever, tiredness, sore throat and swollen lymph nodes, but heals in most cases.

For decades, researchers have suspected a connection between EBV infection and subsequent multiple sclerosis (MS). In the case of the incurable autoimmune disease, which in Germany according to the German Multiple Sclerosis Society (DMSG) affects around 250,000 people, the immune system in the central nervous system destroys the protective myelin sheaths that surround nerve fibers. This leads, among other things, to sensory disturbances, visual impairments and movement problems through to paralysis, which can severely limit the quality of life of those affected.

The team led by epidemiologist Alberto Ascherio from Harvard University has now examined the role of EBV using data from more than ten million young employees of the US armed forces who regularly checked up between 1993 and 2013 HIV had been examined. 955 participants were diagnosed with MS while employed in the military. The researchers looked for antibodies against EBV and other viruses in the blood samples kept from these patients in order to determine which pathogens the patients had been in contact with before the onset of the disease.

First, the researchers examined the last blood sample taken before the onset of the disease in 801 of the MS patients. All but one patient had antibodies to EBV, meaning they had had a previous EBV infection. The time between infection and diagnosis varied greatly and was an estimated 7.5 years on average.

“The study is a milestone”

In the case of the only patient whose blood samples did not contain EBV antibodies, the researchers still do not rule out an infection with the pathogen. It is possible that the participant only became infected after the last blood sample was taken or that no corresponding antibodies were formed. It could also be an MS misdiagnosis, they write.

The authors assume that infection with the virus increases the risk of multiple sclerosis by a factor of 32. This strongly suggests that the pathogen is a cause of the disease – and not just an accompanying phenomenon.

This is all the more true since the researchers also examined the blood samples for antibodies against other viruses – such as the cytomegalovirus, which is also a herpes virus and is transmitted through saliva in a similar way to EBV. The team found no connection here.

The researchers write that other known MS influencing factors could not explain the increase in risk by a factor of 32. The next biggest risk factor the gene variant HLA-DR15, increase the probability of illness by a factor of three. The authors also consider it unlikely that there are still unknown risk factors of the same magnitude as EBV.

“The study is a milestone,” says Ralf Gold, Director of the Neurological Clinic at St. Josef Hospital of the Ruhr University Bochum (RUB) and Chairman of the Medical Advisory Board of the German Multiple Sclerosis Society (DMSG). “You can’t ignore the results.” The results fit, among other things, data on the spread of multiple sclerosis on the Faroe Islands: After British soldiers were stationed there towards the end of the Second World War, the number of cases increased significantly.

However, the exact mechanism is unclear, as explained by William Robinson and Lawrence Steinman from Stanford University in California in a Science comment to write. “Almost everyone is infected with EBV, but only a small fraction develop MS,” they point out. “So other factors such as genetic susceptibility are also important for the development of the disease.” An EBV infection is indeed necessary, but not sufficient on its own to cause the disease.

Two weaknesses of the therapy

MS is to be regarded as a rare late complication of an EBV infection, says the Charité expert Ruprecht. The current study says nothing about the mechanism. “But if we want to better understand how MS develops, that is the central question.”

There are currently a number of assumptions circulating. This includes, for example, that a misguided immune response against the virus ensures that the body’s defenses are directed against components of nerve tracts. But that alone does not convince Ruprecht in view of the widespread spread of the virus: “EBV must cause a specific change in people who later develop multiple sclerosis, flip a molecular switch,” suspects the neurologist.

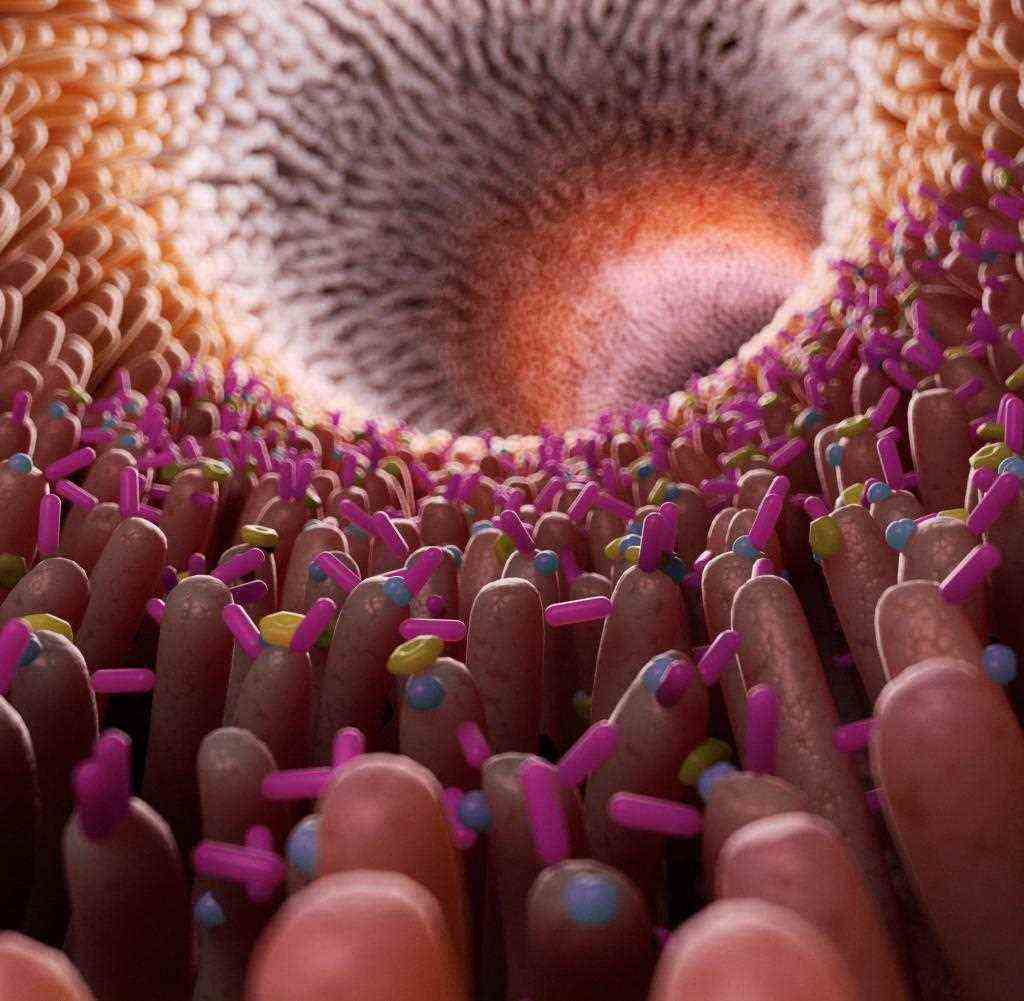

This change presumably affects the B memory cells of the immune system. There are a number of indications that these B cells are involved, most notably the fact that the virus infects these cells and remains there for life.

The suspicion is further supported by a relatively new therapy: antibodies directed against CD-20, a protein on the surface of these B cells. The antibodies kill such B cells in the peripheral blood. “This therapy is very effective, which proves that B cells play a central role in MS,” emphasizes Ruprecht.

Science commentators Robinson and Steinman write that several studies have found EBV-infected B cells in the brains of MS patients. They also refer to the effectiveness of the CD20 antibodies: “The significantly improving effect of B cell degradation in MS clearly proves a central role of B cells in the pathophysiology of the disease.”

At the same time, they point to two weaknesses of the therapy: On the one hand, the antibodies could not get through the blood-brain barrier in sufficient quantities. In addition, they did not reach the precursors of B cells, which do not have CD20.

Therefore, Ascherio’s Harvard team emphasizes that to protect against multiple sclerosis, one must target the Epstein-Barr virus directly, for example through vaccinations. “The extremely low risk of MS in EBV-negative individuals suggests that the vast majority of MS cases are caused by EBV and could potentially be prevented with appropriate vaccination,” they write. In addition, vaccination could also protect against EBV-associated cancers such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Burkitt’s lymphoma.

However, a vaccine is not yet in sight. And Ruprecht basically urges caution: “An EBV vaccination would be the ultimate solution to prevent multiple sclerosis – but only if it reliably and also permanently protects against infection.” Even in this case, it would take decades until finally it would be clear whether such a vaccine would actually provide protection against MS.

However, if a vaccine does not prevent an EBV infection, but only postpones it, the vaccination could even prove to be counterproductive, explains Ruprecht. Because the later in life a person becomes infected with the Epstein-Barr virus, the higher the risk of glandular fever – and also of multiple sclerosis. “Paradoxically, if EBV vaccination in infancy prevented infection for just 10 to 20 years, it could actually lead to an increase in the incidence of multiple sclerosis.”