Much of the plot of Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop is lost to me, though I consider it one of my favorite books. I have a sense that it involves a young priest rising through the ranks of the Catholic Church as New Mexico is flooded by settlers, and I also know that—spoiler alert!—he dies at the end. But what remain indelible are two oddly mathematical vistas. In the novel’s opening pages, a man winds his way through an endless landscape of conical red hills, so alike that “he seemed to be wandering in some geometrical nightmare.” Later, the bishop rides through the country and notices that the world is like a giant mirror: “Every mesa was duplicated by a cloud mesa, like a reflection, which lay motionless above it or moved slowly up from behind it.”

I’ve never been to New Mexico, but I’m half-convinced I have by the clarity of these mental images. That is the power of place in literature, and the closest that prose comes to a magic trick: The best writers can transport you to an utterly different time and location and convince you that you can see it. The believable illusion of a well-written setting is crucial to the workings of storytelling, as Eudora Welty argues in her essay “Place in Fiction.” (Her Collected Stories is included in the list below.) “Fiction is all bound up in the local,” she writes, because “feelings are bound up in place.” The books in this list meld the particular—the quality of the air, say, in Zambia’s Lusaka or the Sahara or a Finnish island—with the abstract and timeless; in short, they capture what it’s like to be alive.

Winter in Sokcho, by Elisa Shua Dusapin (translated by Aneesa Abbas Higgins)

“There wasn’t much to do in the winter” in Sokcho, South Korea, the unnamed narrator points out at the beginning of this compact, vivid novel. It’s a beach town that is bustling in the summer; it also sits just more than 35 miles away from the border with North Korea, and “electrified barbed wire fencing” lines the shore. But the chill and damp that saturate the book are central to its meaning. When a French cartoonist comes to stay at the rundown guesthouse the narrator works at, the two find themselves attracted to each other. Together they visit the DMZ, where the cold makes their eyelids stick to the binoculars that let them peer across the border. They eat fish at a drafty seaside food stall and gaze out at Sokcho from a rooftop in the rain, seeing “a jumble of orange and blue corrugated roofs, the burnt-out ruin of the cinema.” The pipes at the guesthouse freeze. These atmospheric details gesture at a deeper stasis: the narrator’s obligations to her mother that keep her in town, the extended war between the Koreas that keeps their citizens “in a winter that never ends.” “That was Sokcho, always waiting,” the narrator thinks, “for tourists, boats, men, spring.”

The Summer Book, by Tove Jansson (translated by Thomas Teal)

The Summer Book is shelved in the children’s section at my local library, but don’t be fooled by the simplicity of its prose: The novel is painfully profound when it comes to aging and death. Grandmother and young Sophia spend their summers on an island in the Gulf of Finland, making up tales about long-tailed ducks, exploring caves, and arguing about God. Life has an easy, elemental rhythm—the book is composed of vignettes that seem to take place almost outside of time—and yet the story is colored by Grandmother’s dizzy spells and reliance on medication. We slip imperceptibly into the characters’ consciousnesses, particularly Grandmother’s: “The wind was always blowing on this island, from one direction or another … a wild garden for someone growing up, but otherwise just days on top of days, and passing time.” The dead forests, mossy granite, and distant boats are described with the sharpness of lived experience: Jansson herself lived for half of each year on a similar island. Through her characters’ eyes, she conjures the care that stems from decades rooted in a single place, creating an unsentimental yet intimate portrayal of a home.

Stories of the Sahara, by Sanmao (translated by Mike Fu)

In the Chinese-speaking world, the publication of Stories of the Sahara nearly 50 years ago was a literary sensation. Millions of copies have been sold since, in large part because of Sanmao’s wry, approachable, and intensely independent voice. “I’d always felt I wasn’t a part of the world around me,” she writes. “I often needed to go off the tracks of a normal life and do things without explanation”—things such as moving to El Aaiún, the capital of the then–Spanish territory of Western Sahara, propelled by a determination to become “the first female explorer to cross the Sahara.” Instead, her delightful travelogues feel like fables, depicting both the humdrum realities of desert living—the goats that keep falling through the roof of her house, the quirks of the native Sahrawis she and her husband, José, reside with—and the high adventure of escaping quicksand, seeing UFOs, and getting ill perhaps from a possibly cursed necklace. Looking out over the dunes, with their “quiet serenity and profound beauty,” she writes, “inspired an emotion close to pain.” Who wouldn’t be tempted, reading this, to “go off the tracks of a normal life”?

My Garden (Book):, by Jamaica Kincaid

Jamaica Kincaid’s enthusiasm for gardening is contagious, even for someone like me, who has managed to kill a succulent. In the summer, Kincaid writes, she frets about how late her wisterias bloom in her Vermont garden, among her phlox and buddleia and perennial pea, and about a “yellow border” of flowers that simply “does not work.” In the spring, she revels in her fritillarias, which smell like “the underarms of ten people you love.” But gardening for Kincaid isn’t just about tending her plot of land. It’s “an exercise in memory,” and in these short essays, she plumbs the dimensions of her garden beyond its physical realities. Her meditations circle around Antigua, where she was raised: She recalls the soursop tree she was sent to when she misbehaved; the afternoons with her father in the island’s botanical garden, filled with plants from across the British empire and none native to the island itself. Kincaid’s keen awareness of the world outside the garden—that same colonial need for possession shaped the Linnaean system of naming plants, she observes—makes her joy within it all the more satisfying.

The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty, by Eudora Welty

This volume brings together every short story Welty wrote, the large majority of them set in small-town Mississippi. In the collection, women cluster together, opining, helping out at funerals, and fanning themselves waiting for rain; the men go off to drag the river for drowned bodies. The Natchez Trace, the historic trail that cuts through the state, crops up again and again, a wild, difficult, almost mythical road that looms large in the characters’ minds. Welty is famous for much-anthologized stories like the antic “Why I Live at the P.O.,” but her oeuvre is weird and dreamlike, with a pervading aura of secrecy: In one story, a deaf boy forms an attachment to Aaron Burr at the inn where Burr plans his conspiracy; in another, a girl is kept confined by a husband far too old for her in a plot straight out of a fairy tale. In each, Welty’s precise and lavish descriptions of the world abound—a night sky “transparent like grape flesh,” the “embroidering movements” of insects, the Mississippi River “reaching like a somnambulist driven to go in new places.” Every detail seems to hold meaning, to express some facet of the emotional revelations her characters are continually arriving at. Taken together, the stories feel like a glimpse into the humid, shadowed interior of the state itself.

By Eudora Welty

Berlin, by Jason Lutes

In September 1928, two strangers meet on a train headed into Berlin: Marthe Müller, an artist from Cologne looking for her place in the world, and Kurt Severing, a journalist distraught by the dark political forces rending his beloved city. Lutes began this 580-page graphic novel in 1994 and completed it in 2018, and it’s a meticulously researched, gorgeous panoramic view of the last years of the Weimar Republic. The story focuses most attentively on the lives of ordinary Berliners, including Müller, Severing, and two families warped by the increasing chaos. Certain panels even capture the stray thoughts of city dwellers, which float in balloons above their heads as they ride the trams, attend art class, and bake bread. Throughout, Berlin glitters with American jazz and underground gay clubs, all while Communists clash violently with National Socialists in the streets—one party agitating for workers and revolution, the other seething with noxious anti-Semitism and outrage over Germany’s “humiliation” after World War I. On every page are the tensions of a culture on the brink.

The Old Drift, by Namwali Serpell

“This is the story of a nation,” the first page of The Old Drift informs us, “so it begins, of course, with a white man.” The nation is Zambia, and the novel traces three families through four generations and a century’s worth of history, including the country’s independence in 1964, the revolutionary fervor of its aftermath, and the turn to economic privatization in the 1990s. Resonant scenes on the Zambezi River bookend the novel, but the families mainly converge upon Lusaka, the capital city, and illuminate its various crannies—high-end hotels, an Indian wig-seller’s shop, the shacks in the Kalingalinga compound—as the characters’ paths intertwine. One woman sees a representative tableau of the city on display in a government office: “Old men in dark suits; young men in lighter suits; young women in skirt suits; old women in chitenges patterned with staplers, stars, turtles, forks.” Places are created by people, as Serpell suggests with her overflowing, diverse cast—her characters are variously of Italian, British, Bemba, and Indian descent. The infinite ramifications of human conflicts and connections are just as important as the landscape.

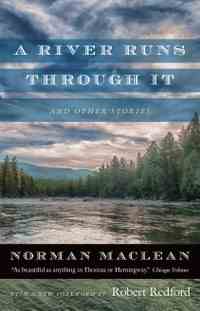

A River Runs Through It and Other Stories, by Norman Maclean

In the years since I first read this collection’s title story, I’ve never been able to think about fly-fishing without a genuine sense of reverence. The story’s narrator (a close stand-in for the real Maclean) has no idea how to help his troubled brother, Paul, who drinks too much and gets picked up by the police with increasing frequency. The most he can do is take Paul fly-fishing, an art they learned from their father, a Presbyterian minister. Maclean dedicates long, languid passages to the finer points of casting in the “great trout rivers” of western Montana, which manage to be both technical and transcendent: “It was one rhythm superimposed upon another, our father’s four-count rhythm of the line and wrist being still the base rhythm. But superimposed upon it was the piston two count of his arm and the long overriding four count of the completed figure eight of his reversed loop. The canyon was glorified by rhythms and colors.” The beauty of the story lies in its specificity—the summer of 1937 on the Big Blackfoot River—against the sweep of religion, the primeval forces of geology, and the pure ache of loving someone whom you struggle to understand.

By Norman Maclean

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.