This experience features music.

Please turn your sound on.

By Tariro Mzezewa

Last March, as New York City became the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic, churches in Harlem closed their doors and silenced their choirs.Last March, as New York City became the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic, churches in Harlem closed their doors and silenced their choirs.

For many churches, this was the first time in their histories that choirs were not able to sing together, in person, on Sundays.For many churches, this was the first time in their histories that choirs were not able to sing together, in person, on Sundays.

At churches like Bethel Gospel Assembly, worship without music was never an option. So leaders found a way to bring the music back. At churches like Bethel Gospel Assembly, worship without music was never an option. So leaders found a way to bring the music back.

This is what it sounds like.This is what it sounds like.

Photographs by Hannah Price for The New York Times

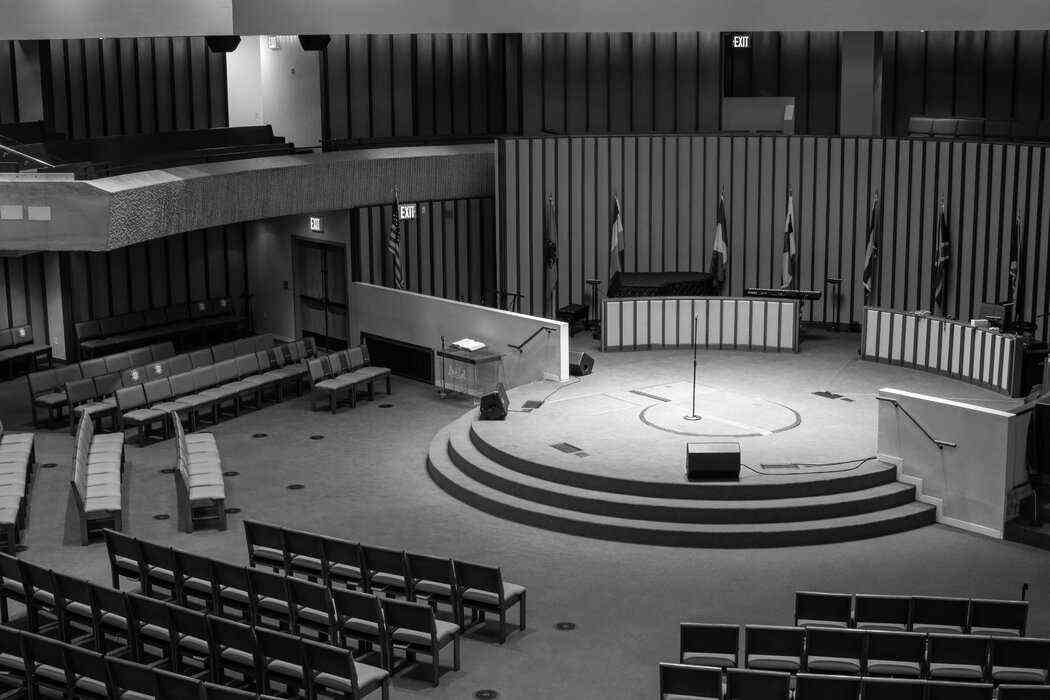

At Bethel Gospel Assembly, a Pentecostal church in Harlem, Sundays once typically began with handshakes, hugs and kisses. The pastor welcomed parishioners from the pulpit to the 2,000-seat sanctuary — his greeting simultaneously relayed in French, Spanish and Italian by translators to accommodate the mostly European tourists who crowded into the church’s balcony to hear the choirs sing.

In Harlem, a neighborhood with hundreds of churches — one of which, Elmendorf Reformed Church, dates back to 1660 — choirs aren’t relegated to backing up the pastor. They are a primary attraction for church members and tourists alike. Many of the local gospel choirs are well-known internationally — the topic of must-see travel lists — and before the pandemic they drew hundreds of visitors each week.

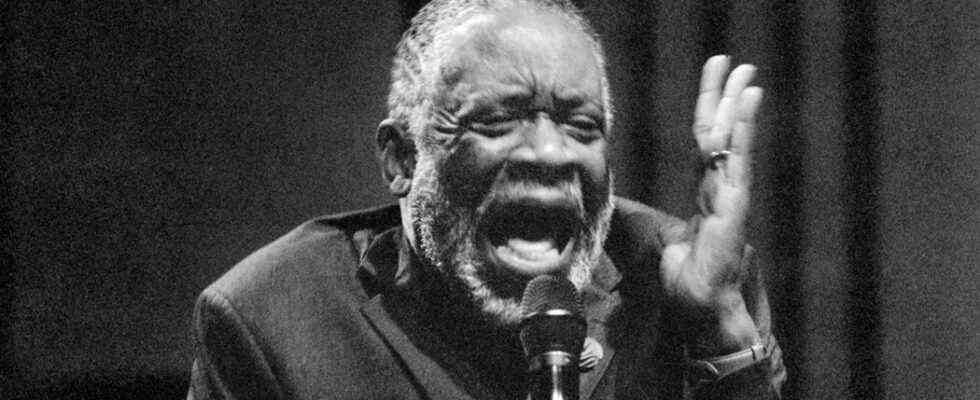

Bishop Carlton T. Brown has been the senior pastor at Bethel Gospel Assembly for 21 years.

That changed the week of March 20, 2020, as pandemic closures went into effect and church leaders including Bishop Carlton T. Brown, Bethel’s senior pastor, told congregants that church doors were closing. Until further notice, services would be streamed online. Which also meant the choirs could no longer gather in person to sing.

“Some would say that, in the United States, you can never shut the church down, the church will always be open here,” Bishop Brown said. “Then all of a sudden we came to a place where the church had to shut down.”

As services moved online, Harlem churches tried different approaches to including music. Some streamed soloists singing from home; others asked choir members to record themselves singing, then combined those videos to play during services.

At Bethel, the church invested in streaming services and saw an increase in online attendance for Sunday and midweek services, with people searching for community during difficult times. The church’s online Bible studies have gone from 20 to 30 students to well over 75 in each class. But many members at churches around the city spoke of missing hearing the live music, which is so central to the worship service. Other churches saw similar increased attendance.

For choirs, singing online was technically challenging; the experience felt disjointed and the results were often disappointing. For churchgoers, watching services from home was lonely. They were grateful for the connection but it wasn’t what it once was. They longed to pray and sing together and they missed the shared experience of worshiping — in particular, the experience of hearing their church choirs.

Left, Dianette Hicks performs during a Sunday service at Bethel. Below, inside Bethel’s sanctuary.

Above, Kiera Yankson, a guest musician, sits in with the band at Bethel. Right, Easter Sunday at Canaan Baptist Church of Christ.

Top left, Dianette Hicks performs during a Sunday service at Bethel. Top right, inside the sanctuary at Bethel. Bottom left, Kiera Yankson, a guest musician, sits in with the band at Bethel. Bottom right, Easter Sunday at Canaan Baptist Church of Christ.

“I remember feeling so awkward not being in the house of God and not actually being able to sing on this pulpit,” said Warren S.L. Hicks, a choir worship leader who has been singing at Bethel since he was a boy. “It was almost like air being sucked out of my lungs.”

Leaders at these Black churches said that cutting music out of services entirely was never an option.

“You can’t have worship completely without music in the Black church,” said Rev. Calvin Otis Butts III of the Abyssinian Baptist Church on 138th Street. “It’s impossible. The Black church is culture bearer, so if you want to have the best of poetry, the best of music, the best of our cultural expressions, you come to the church.”

During the pandemic, being separated from other church members created a sense of loneliness for congregants and choir members. No number of Zoom and FaceTime calls, Facebook Bible studies and streamed Sunday services could make up for not being able to hug someone in person, read a passage from Scripture in unison, hold hands and come together to sing and worship.

For many, church music became a source of strength and a lifeline. Re-establishing that lifeline became a top church priority.

Church leaders in majority Black and Latino Harlem were aware that their community was being affected disproportionately by Covid-19, so they were especially sensitive about the risks of bringing people together again. At Canaan Baptist Church of Christ on 116th Street, more than 40 members of the congregation, including some choir members, died from Covid in 2020.

But church leaders also found that, during a time of fear and uncertainty, churchgoers felt cut off from a source of strength they needed: their community of faith. Not being able to gather and sing together — at funerals, in particular — made the distance from one another feel vast. So they looked for ways to bring live music back.

At the onset of the pandemic, Abyssinian Baptist Church, founded in 1808, began streaming virtual services, and Ramón Bryant Braxton, the director of music, asked soloists to come sing alone, accompanied by musicians, in the empty sanctuary.

By late April 2020, Mr. Braxton had another idea: He assembled additional groups of singers, including a quartet and an ensemble of nine. The groups would sing while socially distanced in the empty church on alternating Sundays.

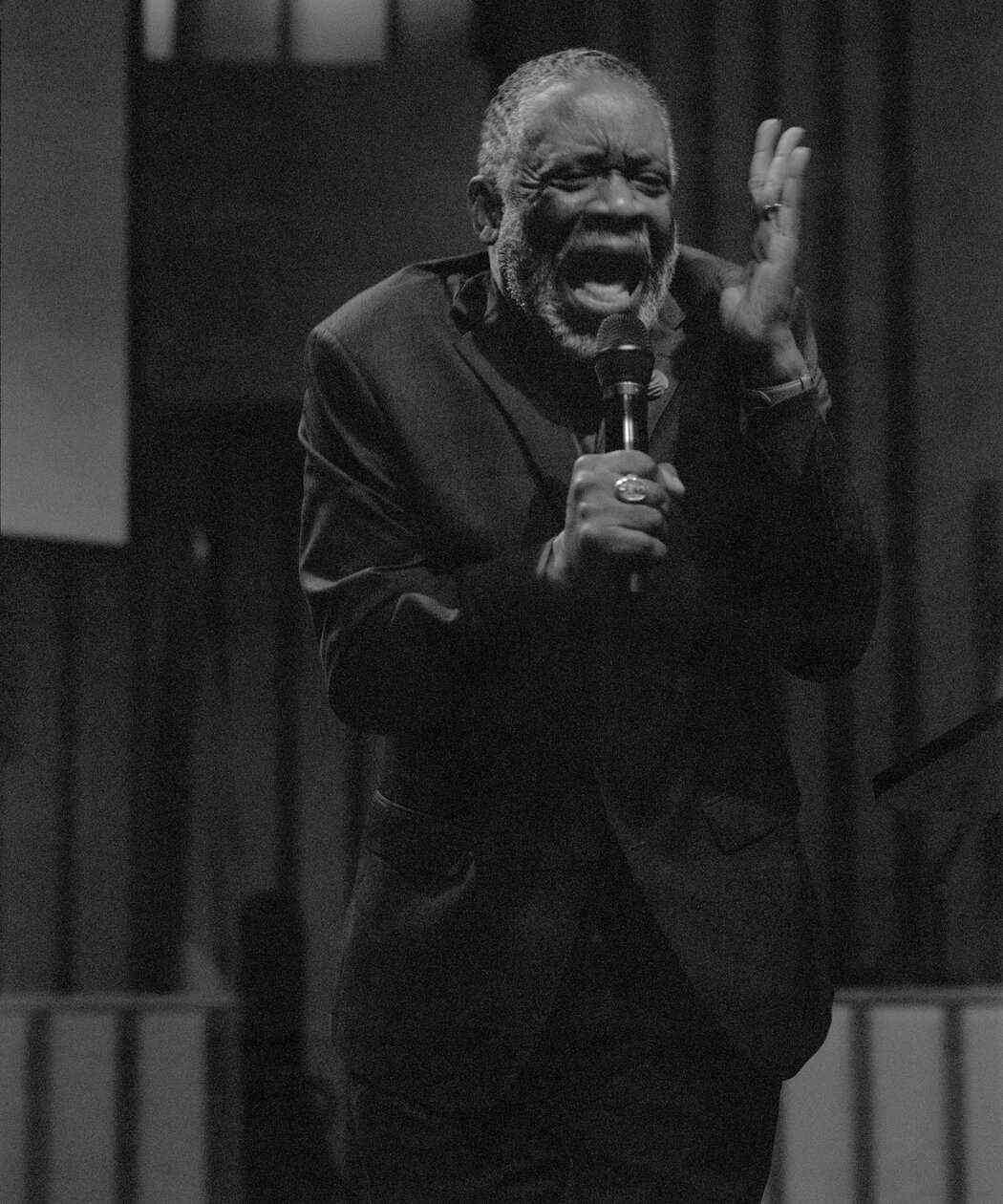

From left, Frederick Myers, George Keller, Lawrence Evans and Ron Presley rehearse at Canaan Baptist Church.

“At one point, we rehearsed in the sanctuary and lined the balcony with the big group of nine spread out,” Mr. Braxton said. “But the challenge was that, because everyone was so far apart, they had to work twice as hard to hear each other. To create the sense of ensemble you can’t be in a vacuum.”

B. Dexter Allgood, the minister of music at Canaan Baptist, said that his church typically had seven different choirs consisting of dozens of singers and that, on any given Sunday before the pandemic, as many as 100 people would sing.

“You have the Word and then you have the Word in song — there’s a connection there, and when it’s not there it feels like a void,” Mr. Allgood said, adding that he doesn’t think that before the pandemic he’d ever spent a single Sunday in his adult life away from a sanctuary.

After trying various methods of keeping music in the service virtually, Mr. Allgood pulled together a group of eight singers to come sing live from the church. Some of them stood socially distanced on the stage, while others would sing while arranged among the empty pews.

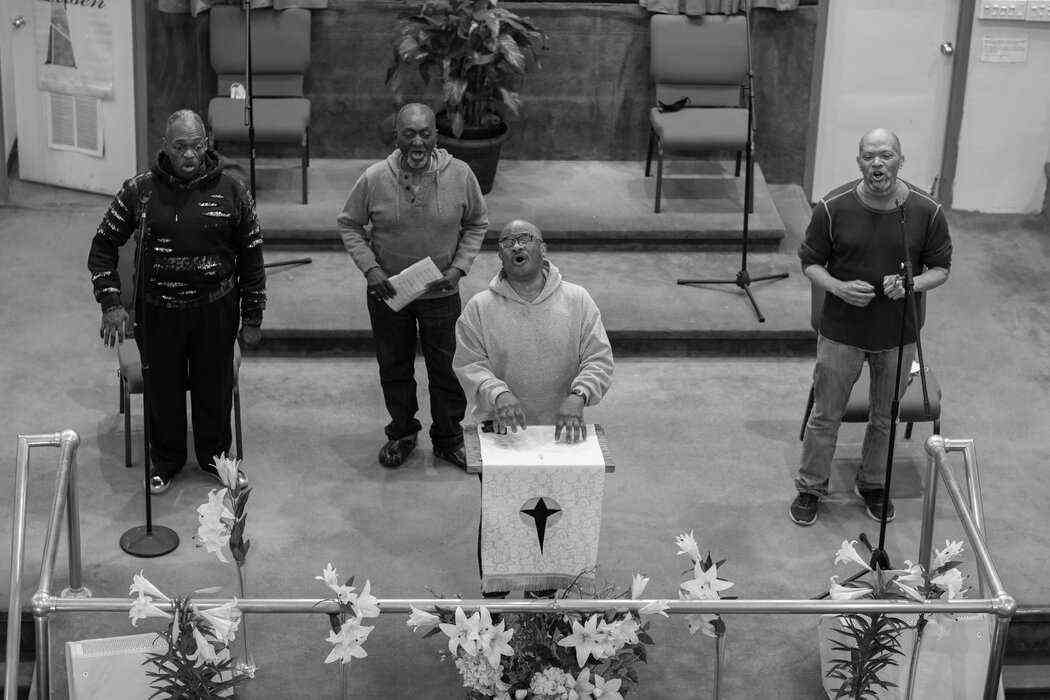

Adrienne Hicks, a singer at Bethel, during a recent rehearsal.

Reuniting to sing together, even while distanced, allowed choir members to once again feel a sense of community.

“You think people get together because we all like to sing? Not necessarily,” said Frederick Myers, a singer at Canaan who also sings professionally. “They get together because they need somebody to talk to. It’s more counseling sometimes. You have an outlet and, once you have that person in the choir that you can talk to, you can sing because there’s somebody there who cares about what happened to you today.”

Mr. Myers has Stage 3 cancer and said that church music, and choral music in particular, has kept him going over the past year.

Mr. Hicks has been singing at Bethel for 30 years. His parents and his wife, Adrienne, are involved in Bethel’s music ministry. Ms. Hicks’s father directed the youth ensemble in the 1970s and ’80s, and her mother directed the children’s choir. She and Mr. Hicks met at the church 33 years ago.

These kinds of family connections aren’t rare in churches and among their choir members. Choirs at Black churches often include family members of multiple generations, and, in many cases, choir members became so close that they considered each other family.

During the week, Mr. Hicks is a manager at the emergency department at NYC Health + Hospitals in Harlem. The early days of the pandemic took a toll.

“When I couldn’t be in the sanctuary on a Sunday and I was in work pushing dead bodies,” said Mr. Hicks, “it was important for me to have something in my ear to keep me going, and those were the songs, songs of the Lord.”

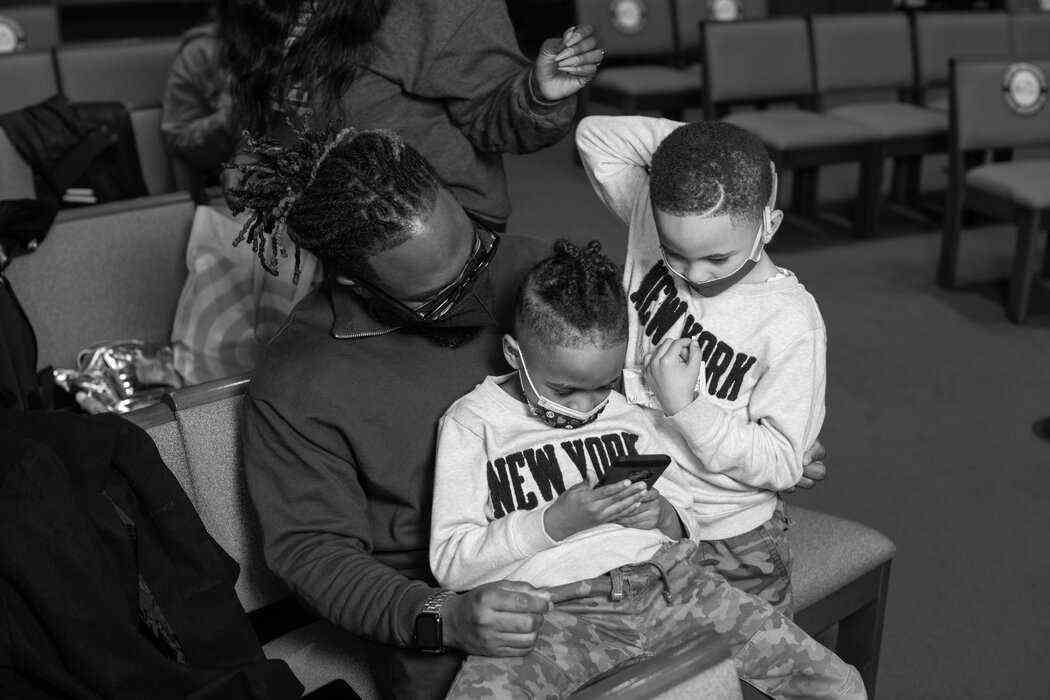

Left, Chris Anthony, a guest singer at Bethel, takes a break during a rehearsal with the sons of a fellow performer. Below, Warren Hicks, a praise-team leader, rehearses at Bethel.

Above, Rebekah Gordon sings during a socially distanced Sunday service at Bethel. Right, Easter Sunday at Canaan Baptist Church.

Top left, Chris Anthony, a guest singer at Bethel, takes a break during a rehearsal with the sons of a fellow performer. Top right, Warren Hicks, a praise-team leader, rehearses at Bethel. Bottom left, Rebekah Gordon performs during a socially distanced Sunday service at Bethel. Bottom right, Easter Sunday at Canaan Baptist Church.

On the recent Easter Sunday, Renay Peters Joubert, a professional singer who has been at Abyssinian Baptist Church off and on for 15 years, returned to the church to sing an arrangement by her husband, Joseph Joubert, who accompanied her on piano. Services at Abyssinian hadn’t yet opened to congregants, marking a second Easter away from the church for many worshipers.

“It’s my whole being, the church music,” Mrs. Joubert said. “It just gives me that sense of calm, and that’s the only thing that really got me through this pandemic.”

At Bethel in the fall, Bishop Brown, feeling the strain of isolation in the community, decided to bring back in-person services with limited attendees. Safety was a priority. Only 50 parishioners could be in the church, which typically seats 2,000. The church did a soft opening in October and opened with a few members in mid-November for its 103rd anniversary.

As restrictions in the city have lifted and more people have been vaccinated, the churches are welcoming limited numbers of parishioners back into the pews.

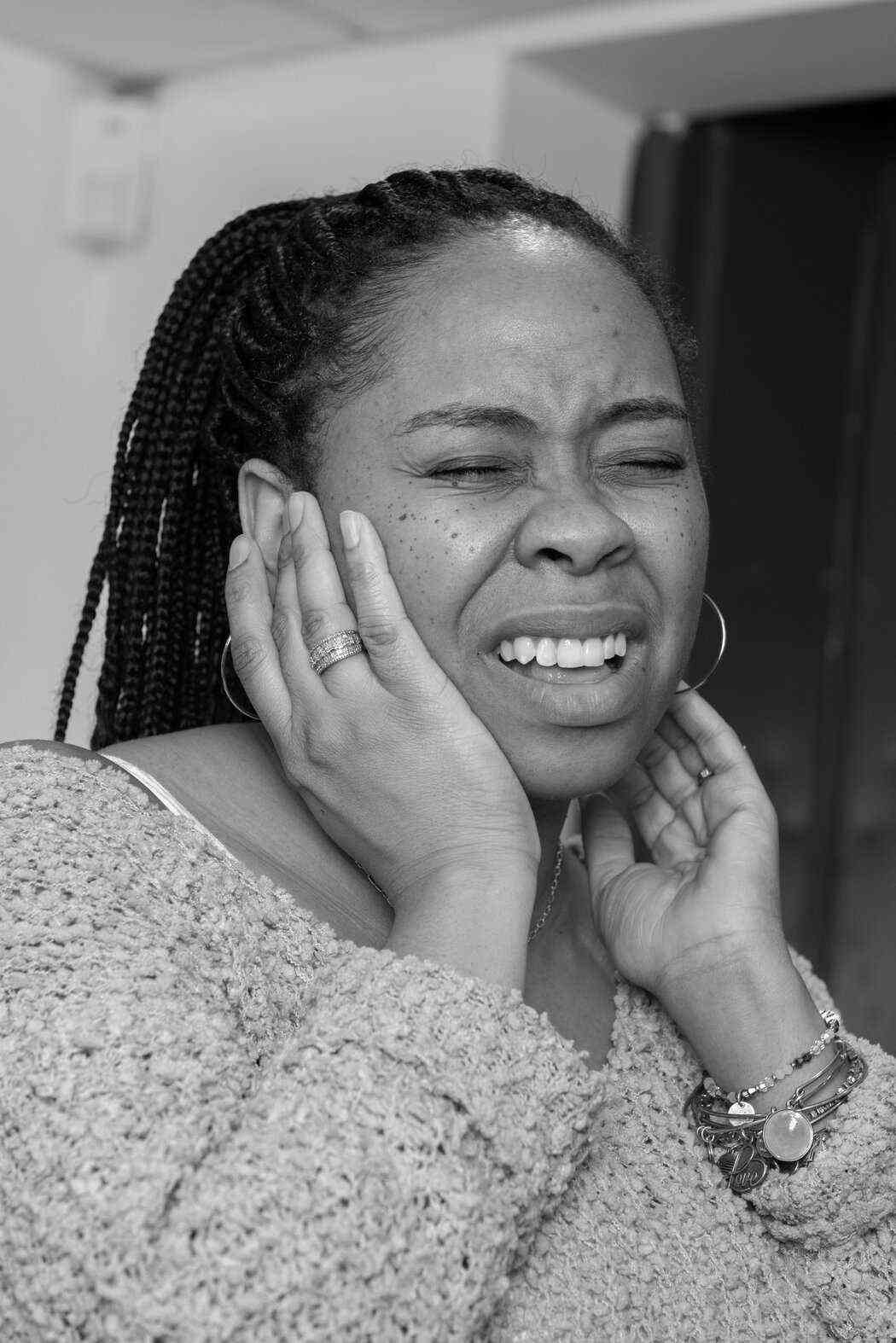

“You don’t know how it felt to just walk into that sanctuary again,” said Rita Williams, 59, who has been singing in three of Canaan Baptist Church’s choirs for seven years and who works as an emergency room technician at Mount Sinai Hospital. “I just had this peace and comfort.”

The experience isn’t yet what it once was — elbow bumps have replaced hugs and kisses; singers don’t share microphones; masks have to stay on. Most churches have changed how they observe communion. Those coming to church on Sunday have to register online and provide declarations ensuring that they are not displaying coronavirus symptoms. Once they arrive, temperatures are scanned and stickers displayed on pews to maintain social distance.

Members of the church’s dance ministry on a Sunday at Canaan Baptist Church.

But it’s all worth it for a chance to worship together again.

“We need to share our experience and how we got through this. We need that support from one another,” Ms. Williams said.

The pews are not yet full and the choirs aren’t back to full strength. But the churches are once again hosting gospel music and the churchgoers who missed it.

“I still miss looking out and seeing everyone singing in the pews, and I miss when the Holy Spirit come down,” Ms. Williams said. “I’m waiting for that day when the doors can open and we can all come in shouting and singing ‘Hallelujah, praise God, thank you, Jesus’ — especially those of us who made it through the pandemic.”

Bethel Gospel Assembly

Senior Pastor

Bishop Carlton T. Brown

Executive Pastor

Ruth-Ann Wynter

Singers

Chris Anthony

Michelle Clark

Lia Ferguson

Rebekah Gordon

Warren S. L. Hicks

Adrienne Hicks

Sheherazade Holman – Soloist

Jayvon Roberts

Band

Carl Antoine – Percussion

D. Leon Brown – Organ

Travis Davis – Drums

Chelton Grey – Bass

Brandyn Porter – Guitar

Lester Robinson Jr – Keys

Robert Soverall – Piano

Sound

Chris Green

Terrence Friday

Project Credits

Edited by Marcelle Hopkins, Adam Sternbergh, Jennifer Harlan, Dodai Stewart and Veronica Chambers. Designed by Michael Beswetherick and Danny DeBelius. Produced by Sukanya Aneja, Mint Boonyapanachoti, Jon Cohrs, Evan Grothjan, Niko Koppel, Guglielmo Mattioli, Avner Peled, Miles Peyton and Guilherme Rambelli. Photo editing by Amanda Webster. Audio recorded and mixed by Jon Cohrs. Augmented reality experience by Nicholas Bartzokas, Evan Grothjan, Lydia Jessup, Miles Peyton and Noah Pisner. Additional support from David Klopfenstein, Jeremy Allen, Lauren Messman and Lauren Reddy.