This article is part of T’s Book Club, a series of articles and events dedicated to classic works of American literature. Click here to R.S.V.P. to a virtual conversation about “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” to be led by Edmund White and held on April 22.

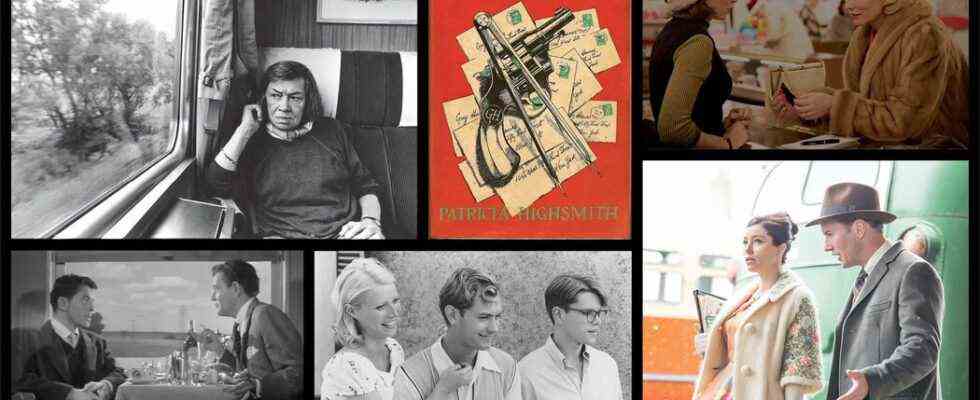

Toward the end of her life, in a 1987 interview with Terry Gross, Patricia Highsmith denied what a biography of Alfred Hitchcock claimed the director had once said to her about his 1951 adaptation of her novel “Strangers on a Train” — namely, that she should pay him for making the film, since it would have a great effect on her career. “No,” Highsmith scoffed, her voice husky from the many cigarettes and martinis to which she was partial. “I never had such a personal conversation with Mr. Hitchcock.” Still, Hitchcock’s film catapulted Highsmith to new heights. It also kicked off a long tradition of her work being adapted for the screen that would continue well after her death, in 1995. Today, there are at least 20 adaptations for film and television based on Highsmith’s novels and stories — not including Showtime’s forthcoming “Ripley” series, starring Andrew Scott and Dakota Fanning. There are many reasons Highsmith’s psychological thrillers lend themselves so well to cinema. They are suspenseful and dramatic, frequently set in glamorous locations (the Amalfi coast, Rome, Paris). Throughout, there is often a strong current of sexual tension (Highsmith herself was a lesbian) and an expressed desire to belong to the world of the wealthy and elite. Her characters are also granted charm, uncanny intelligence and first-rate seduction skills, as well as murderous urges, and are thus as villainous as they are entrancing. But Highsmith perhaps knew best what fiction could accomplish better than any movie, asserting: “What I can do in the way of words to show the internal workings of a person’s mind cannot be done in film.” Though the results vary, her writing has undoubtedly given directors plenty to work with. Here, an examination of four cinematic interpretations — good and bad — of Highsmith’s books.

“Strangers on a Train” (1951)

Adapted from Patricia Highsmith’s “Strangers on a Train” (1950)

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Screenplay: Raymond Chandler, Czenzi Ormonde; adaptation by Whitfield Cook

Starring: Farley Granger, Robert Walker, Ruth Roman

On a New York-bound train, socialite Bruno Antony (Robert Walker) tells tennis star Guy Haines (Farley Granger) that he admires “people who do things” because he never seems “to do anything.” Bruno does, however, concoct a scheme to swap murders with his new acquaintance: He will kill Guy’s cheating not-yet-ex-wife, Miriam, thus freeing Guy to marry his new love, Anne (Ruth Roman). Guy, in turn, will kill Bruno’s much-loathed father. Both, Bruno promises, will get away with their respective crimes because no one will suspect them: Neither has a discernible motive. Disembarking the train (but fatefully forgetting his engraved cigarette lighter, which Bruno will eventually use to blackmail him), Guy laughs the scheme off, dismissing Bruno as crazy. He assumes that’s the end of it.

Of course, it’s just the beginning. Bruno finds and strangles Miriam. Naturally, Guy, as the estranged husband, is the police’s prime suspect; Bruno exploits this predicament in his concerted efforts to force Guy’s hand to murder his father in exchange. Various aural, visual and sartorial clues tell us that Bruno’s attraction to Guy is fueled as much, if not more, by Eros as by Thanatos. Bruno is a gossipy mama’s boy who is fond of tailored suits and silk robes. The queer subtext is barely below the surface — just far enough to get past Hollywood’s Hays Code censors of the day. And Granger and Walker’s onscreen chemistry is palpable.

Strangers though Guy and Bruno might be, Hitchcock reminds us from the outset (and through every plot twist and turn) that they are also doppelgängers. His visual and verbal play with doubling is delightfully hyperbolic. In the first few minutes of the film, there are two sets of legs and shoes, two taxis, two porters, train tracks that crisscross twice — such examples proliferate throughout the film and are echoed in Hitchcock’s use of reflections, crosscutting and dissolves, which further emphasize the extent to which Bruno and Guy are forcefully and inextricably connected.

There is less murder but more mayhem in Hitchcock’s adaptation of Highsmith’s novel. The film is also more expansive, existential and contemplative. Where the book has just one major amusement park scene (in which Miriam is murdered), the film adds a second as the site of its chaotic climax (the merry-go-round runs amok, killing Bruno) and denouement (the police discover Guy’s lighter in Bruno’s dead hand, proving that Bruno is the culprit). Guy is ultimately exonerated. The film concludes by mirroring its beginning but adds a humorous touch: Guy and Anne exchange glances before switching train cars to avoid a kindly stranger who recognizes them.

There are no such light touches in Highsmith’s novel, in which both men are murderers. Guy (here an architect, not a tennis star) succumbs to Bruno’s pressure and murders Bruno’s father precisely as instructed (in the film, he tries to warn the father that his son is a maniac). Later, Bruno dies in a boating accident and Guy, racked with guilt, confesses. If Hitchcock’s moral vision is as black-and-white as his cinematography, the novel paints exclusively in shades of gray, reveling in moral and ethical ambiguities. Highsmith’s vision is less sensational and, as a result, more sinister. Hitchcock’s characters are either good or evil; Highsmith reminds us that everyone is both at once, and that anyone could be capable of murder.

“Carol” (2015)

Adapted from Patricia Highsmith’s “The Price of Salt,” published in 1952 under the pseudonym Claire Morgan

Director: Todd Haynes

Screenplay: Phyllis Nagy

Starring: Cate Blanchett, Rooney Mara, Sarah Paulson, Kyle Chandler

Department store salesgirl and photographer Therese Belivet (Rooney Mara) is instantly enthralled by a new customer, the wealthy (almost) divorcée Carol Aird (Cate Blanchett). The pair embark on a friendship turned romance that irrevocably alters both their lives. Lesbians everywhere hold their breath until the film’s end: Here, neither woman is killed off or declared insane — rare in most Hollywood depictions of queer female love. Moreover, the novel and its film adaptation give them a refreshingly hopeful conclusion. This love affair just might stand the test of time.

In director Todd Haynes’s hands, though, everyone is domesticated. “Carol” refuses its characters their original sharp angles and dark corners. Haynes’s Carol transforms from the novel’s exceedingly confident, often cold, sometimes calculating protagonist into a soft, yearning and ultimately martyr-like mother. Her ex-husband, Harge (Kyle Chandler), is rendered too sympathetically: He hovers and beseeches where in the novel he schemes and withholds. We witness film Harge fixing a pipe under the sink in the house to which he desperately longs to return, declaring his love for Carol in multiple scenes and looking anguished by Carol’s sacrifice in granting him full custody of their daughter, Rindy. Highsmith’s Harge isn’t given that much time or attention: His attachment to Carol is expressed predominantly as possessive patriarchal entitlement and an ego-driven desire to save face.

Film Carol sips tea and decorates the Christmas tree; she wraps presents and fusses over her daughter. In an anticlimactic scene that feels more like a slumber party than the exciting beginning of a night of seduction, Carol gives Therese a … makeover. And while we know their feelings run deeper than friendship, this isn’t because of any great chemistry between the two leads, which is sadly lacking, save during their (yes, hot) sex. Conversely, novel Carol is alluringly opaque. Rarely without a drink or cigarette in hand, she declines to reassure Therese about her feelings or their future.

While Haynes uses hands as a gorgeous leitmotif in “Carol” — giving them many lingering close-ups — they don’t do as much as they do in the novel. There, Therese is an assured and ambitious set designer ready to make her mark in the field; she’s a builder of fantastic worlds. But in the film, she is an insecure photographer who documents rather than creates scenes; her novelistic counterpart simply could not afford such a career. The stark class (and age) differences between Therese and Carol are salient and profound plot points in the book. The film confronts them less directly.

Made more than 60 years after the novel was published, the film reflects surprisingly conservative choices about its characters, making them out to be simpler and ostensibly more palatable at every turn. Film Therese is even a virgin, whereas novel Therese is having (unsatisfying) sex with her putative boyfriend, Richard. The hard, fierce underplay of emotions and issues that Highsmith so carefully wrought is here treated like (unsalted) butter on the counter, left to soften until easily spread.

“A Kind of Murder” (2016)

Adapted from Patricia Highsmith’s “The Blunderer” (1954)

Director: Andy Goddard

Screenplay: Susan Boyd

Starring: Patrick Wilson, Jessica Biel, Eddie Marsan, Vincent Kartheiser

“A Kind of Murder” is kind of a terrible film — a noir thriller with no teeth, unless you count Vincent Kartheiser (as Detective Corby) chewing the scenery. Kartheiser’s hokey, overzealous acting embodies all that doesn’t work here. The film turns psychologically complex characters into one-dimensional caricatures, and Highsmith’s nuance, suspense and tension — which manage to create claustrophobic worlds in wide-open spaces — are nowhere to be found. Heavy-handedness does not help director Andy Goddard’s cause: He’s about as subtle as the ubiquitous, lurid reds (curtains, walls, bedspreads) that color the film’s depiction of 1960s New York. We get it: Someone has blood on his hands.

Walter Stackhouse (Patrick Wilson) is unhappily married to a neurotic, paranoid and icy real estate agent named Clara (Jessica Biel), whom he finally decides to divorce. When Clara turns up dead under a bridge near Harry’s Rainbow Grill, Corby is convinced Stackhouse killed her; moreover, he’s sure Stackhouse has followed in the footsteps of local bookstore owner Marty Kimmel (Eddie Marsan), whose wife, Helen, was recently found murdered at the same location. Copycat or coincidence? In the novel, Kimmel has brutally murdered his cheating wife, Helen, by the end of the first chapter, making Stackhouse’s obsession with this story and his repeated visits to Kimmel’s shop compellingly suspect, even hinting at possible collusion. Is Kimmel Stackhouse’s murderous mentor? In the film, we don’t know for sure that Kimmel is guilty until a flashback much later in the plot shows him committing the crime, and so the encounters between the strangers come off as decidedly less fraught. Stackhouse’s fascination with Kimmel — he just can’t keep his distance — isn’t quite earned here.

In the novel, Stackhouse is a lawyer and amateur writer working on a book of essays titled “Unworthy Friendships,” whose thesis is that most people maintain friendships with at least one person inferior to themselves. He happily writes for his own pleasure, not caring whether the work is published. Film Stackhouse is an architect and amateur writer of crime fiction (inspired by true stories he clips from newspapers) who’s eager for a byline. In theory, this metafictional angle is rife with possibilities; in practice, however, it’s a rather moot plot point. Aside from close-ups of Stackhouse banging out provocative, potentially revealing text on his typewriter, the film does nothing with it. This feels like a missed opportunity to say more about the slippery relationship between fact and fiction and the potentially dangerous allure of true crime.

As a title, “The Blunderer” is wonderfully onomatopoeic; it’s also a phrase that refers predominantly but not exclusively to Stackhouse, as he commits error after error in the wake of Clara’s death; his attempts to prove his innocence continue to implicate him and his life spirals out of control. He loses his friends, his job, his new girlfriend and more. We never learn whether Stackhouse is guilty in either the novel or the film. But in Highsmith’s hands, this ambiguity satisfies, because her blurring of the boundaries between fantasy and reality is thought-provoking and profound.

“The Talented Mr. Ripley” (1999)

Adapted from Patricia Highsmith’s “The Talented Mr. Ripley” (1955)

Director: Anthony Minghella

Screenplay: Anthony Minghella

Starring: Matt Damon, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, Philip Seymour Hoffman

Early on in the film, Dickie Greenleaf (Jude Law) declares that “everybody should have one talent” and asks Tom Ripley (Matt Damon): “What’s yours?” Without missing a beat, and in one of many sharp departures from Highsmith’s novel, Tom responds, “Forging signatures, telling lies, impersonating practically anybody.” Why does the con man admit to being a con man? Is it just another part of the trick — or a genuine attempt to be seen for who he really is? Director Anthony Minghella’s choice to highlight this passage from the book amplifies, rather than flattens, Highsmith’s themes; this is the real achievement of his gorgeous adaptation.

In Minghella’s world, Tom already plays many parts — he stands in for a piano player at a fancy party; he’s caught taking the stage after hours at the concert hall where he’s employed as a lavatory attendant. Minghella shows Tom working hard, whereas in the novel, he is resentful of having to do so. Film Tom studies up before his trip to Italy to bring Dickie home (at the behest and expense of Dickie’s father) — he learns about jazz to forge common ground with the rich and cultured Dickie (here an amateur musician rather than painter). While the movie omits Tom’s upbringing with a horribly homophobic Aunt Dottie, on whom he’s begrudgingly dependent, it also shows Tom to be a sympathetic working-class striver. “I always thought it would be better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody,” he explains.

If film Tom is more sympathetic than his novel equivalent, some of his victims, Dickie and Freddie Miles (Philip Seymour Hoffman), are less so — they are mean and bullying snobs who ridicule Tom’s lack of wealth and worldliness, excluding him from their group trip because he doesn’t know how to ski. They are also eminently more disposable, and as a result their deaths are not as shocking or sad. Film Dickie is engaged to Marge Sherwood (Gwyneth Paltrow) while also carrying on with a pregnant Italian lover who dies by suicide. In the novel, Marge’s love for Dickie is unrequited and a little pathetic. Still, both versions capture what Tom can never earn for himself: the cruel sense of entitlement that comes with privilege.

The film aggressively tries to socialize Tom, giving him a flirtatious relationship with an heiress named Meredith Logue (Cate Blanchett), a companionable vibe with Marge (completely absent in the novel, where she’s his stark antagonist) and, toward the end, even a loving, attentive boyfriend, Peter (whom, yes, he must kill so as not to be caught for impersonating Dickie). The novel’s Tom is singular, solitary, alone in a crowd — seemingly only alive when his impressions and actions are viewed positively in the eyes of others.

The opening credits offer a roulette wheel of adjectives (“mysterious,” “troubled,” “yearning,” “secretive,” “lonely,” “gifted,” “confused,” “loving,” “intelligent,” “haunted,” etc.) before landing on “talented.” Damon’s portrayal of the title character — which calls for him to embody all these traits simultaneously — is convincingly nuanced. His Tom is drawn to and tortured by the sundry selves he encounters and creates, at one point riding a moped down an alley of mirrors that seem to taunt him, until he crashes. Of course, one of the mirrors shatters, and he sees himself in the same fragmented manner that we do.

“The Talented Mr. Ripley” is arguably the best and most renowned adaptation of any Highsmith work to date owing to the superb cast — everyone is so eminently watchable — and to Minghella’s care with his source material. As any filmmaker must, he adds and subtracts details, but he never sacrifices Highsmith’s smooth surfaces or the depths that they only occasionally disguise.

Kerry Manders is a writer, editor and photographer whose personal work focuses on queer memory and mourning.