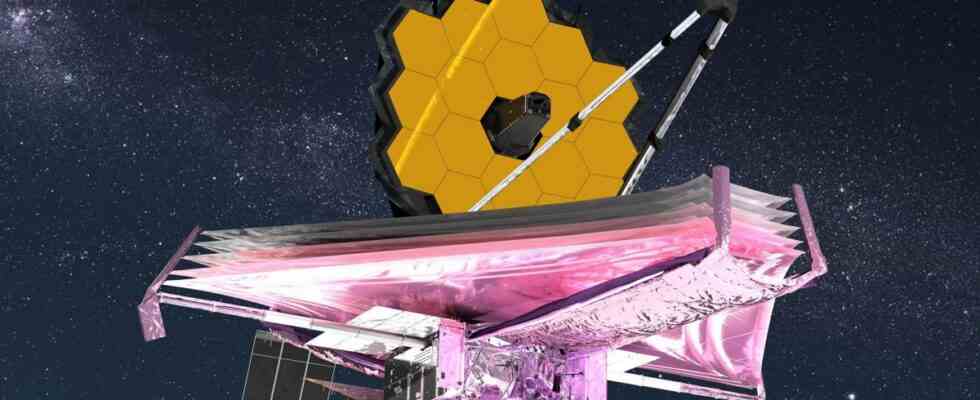

NASA’s consideration of making images taken by the James Webb Space Telescope public in the future has met with mixed reactions among astronomers. While some criticize that small research institutions and researchers with many other obligations in particular could be disadvantaged, others hope that the “locked away” data will be made available more quickly.

Both sides have comprehensible arguments and it is currently not foreseeable how the debate could end. The Space Telescope Institute, which is responsible for the scientific operation of the James Webb space telescope, also wants to interview 12,000 researchers directly, writes the science magazine Science.

A head start for those with the ideas

Currently, observatories for general research, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) or Hubble, have embargo periods during which researchers have exclusive access to the data collected in response to their suggestions. The periods are typically between 6 and 18 months long. At Hubble, for example, the deadline has been reduced to six months after it had been a year for a long time.

During this period, those who proposed the respective measurement can evaluate the collected data without having to fear that someone will forestall them with the publication of a scientific article. There is currently an exception with the JWST, the data collected in the first five months are released here directly. The aim is for the scientific community to learn how to use the new observatory and its instruments as well as possible.

Accelerate research

As Science explains, NASA’s considerations are based, among other things, on new specifications from the US government. It announced in August that all state-funded research should be freely available immediately after publication from 2026. The US space agency, as the main person responsible for the space telescope, could therefore have to lift the restrictions. However, this is opposed, among other things, by obligations to Europe’s space agency ESA and the Canadian CSA, which are involved in the project.

also read

A practical argument for the abolition of the blocking period is the possible acceleration of work. When observing data becomes public immediately, research teams can quickly plan further measurements and request new observing time. That seemed important, especially when it had to be assumed that the JWST would only be able to work for a few years. In view of the now foreseeable, significantly longer mission duration, the argument loses some of its weight.

Disadvantage for the little ones

At Scientific American, US astronomer Jason Wright counters thisthat the pressure to work with publicly available data might be too great. Thoroughness could suffer if you have to worry that someone else is faster. He is not convinced by the argument that disadvantaged institutions would have the same opportunity to conduct research if they were given direct approval. Ultimately, they would always lose to large, financially better off institutions under these circumstances. Because they would have the most resources to always be faster, even with measurements based on the ideas of others. And researchers who also teach, for example, or who for other reasons cannot simply work night shift after night shift, would then no longer be able to keep up.

If the embargo is indeed lifted, astronomy will have to come up with new ways to recognize those who propose certain observations, Wright said. For example, it could become mandatory to always list them as co-authors of a specialist article. Or any scientific article that relies on measurement data might need to state whose suggestion it was collected. But all of that would just be adjustments that don’t solve the fundamental problem, he says. For astronomers, too much is attached to scientific publications to deprive them of the protection offered by the embargo period.

(mho)