A story about Deutsche Bahn cannot begin without a complaint, because of the recognition effect. So let’s ask Mr. G. Halle, a businessman from Leipzig, who lives in the pretty Hardenbergstrasse, whether he enjoyed his journey on the express train to Munich. He didn’t. How could he?

It was like this. At exactly 10.21 a.m. Mr. Halle arrived at his destination station, having boarded early in the morning in his home town, carriage four, seat 30, second class. He wrote his entry in the Munich rail complaints book at 10.56 a.m., it seems someone had a lot of pressure on their pen. And how could it be otherwise? Mr. Halle had to look for a “washing facility” on his train between 7 and 7.30 a.m. – for a full 30 minutes. And the fact that Mr. Halle calls this a “washing facility” in the complaints book shows that Mr. Halle is by no means one of the louts. Not at all! Mr. Halle is not complaining with cheap polemics about a rolling institution for preventing the gratification of needs. No, he, Mr. Halle, wanted to find a washing facility, just a washing facility.

Before we have to investigate Mr Halle’s railway complaint further: we are in the exhibition “Under Pressure” in the DB Museum in Nuremberg, which is finally addressing a glaring research gap: the history of the train toilet.

Mr. Halle? In his human distress – which he does not name, but sticks to washing purely out of goodwill – he “while searching,” as he puts it, ended up in a sleeping car, complete with a toilet. But before Mr. Halle could get started, an “official on duty” knocked on the washroom door, Mr. Halle opened it and was asked to leave the premises “in a very rude manner” (this was clearly highlighted by Mr. Halle in the complaints book). The reason is not specifically stated, but it can be assumed that Mr. Halle had unfortunately not purchased the shared use of the corresponding sleeping car washing facility in his train package.

Whatever the case, at 9 o’clock – and thus two hours after Mr. Halle had begun to feel the need to wash – the train staff “instructed him to use the toilet in another carriage.” And Mr. Halle? Reacted as is his wont: with a tip.

The complaint concludes: Mr. Halle does not believe that it is in the interests of railway personnel to be “treated so roughly” when travelling and he requests the responsible authority “respectfully to subject the matter to a thorough investigation.” Mr. Halle also encloses his seat reservation with the complaint as evidence.

The entry in the railway complaints book dates back to June 1908 – and of course, as the DB exhibition in question clearly proves, Deutsche Bahn is now a step ahead in terms of service, friendliness and average washroom waiting times. But it is somehow interesting what Mr Halle has to say about 116 years ago.

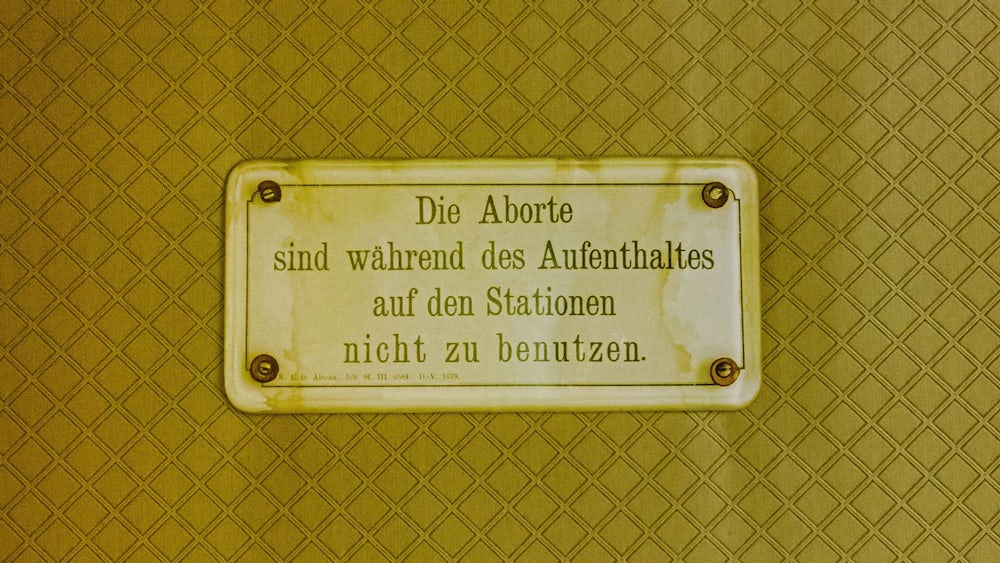

And yes, visiting this exhibition will help to ease the unrest in the hearts of current rail travellers. It is proven that it is no longer necessary to use a boot or hat as a train toilet, as the Fürth doctor Dr. Fronmüller criticized in 1855. The ingenious downpipe solution, along with the corresponding hygienic track systems and the sign that was still popular in the Kohl era, “Please do not use the toilet while the train is at a station”, is also clearly a thing of the past.

Even the “very rude manner” of turning people away from the DB washroom is no longer to be seen. Perhaps – of course, we don’t know – Mr. Halle’s entry in the book contributed to this.