For some years now, books have been popular that look at historical events as if through a prism, revealing a multitude of fates, stories and surprising connections. Florian Illies’ pre-war kaleidoscope “1913” was the beginning of this form of visualizing partly known, partly forgotten events, the clever combination of which produces an almost new type of historical picture.

The literary critic Uwe Wittstock has made this procedure his own and in “February 33 – The Winter of Literature” tells of the beginning of the synchronization of the German literary industry and the rapid destruction and expulsion of the intellectual elite of the Weimar Republic. It is a startling and poignant book because, using the example of such different, even contradicting writers such as Gottfried Benn, Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Else Lasker-Schüler and Ricarda Huch, it shows how resolute and brutal the cultural policy of the Third Reich was from the beginning the ideal and physical annihilation of those artists and writers whose person and work opposed the regime and its ideological objectives.

Wittstock is a clever and conscientious narrator who knows that historical facts cannot do without associative leeway. The material from which his great story of the decline of a great literary epoch is woven is from the written memories of the writers, theater people and journalists of those years. They give his descriptions the color and a sound of contemporaneity, which Wittstock strikes with admirable carelessness and which puts the already dramatic events under a fascinating narrative tension.

The highly networked society of the successful suspects, knows, suppresses

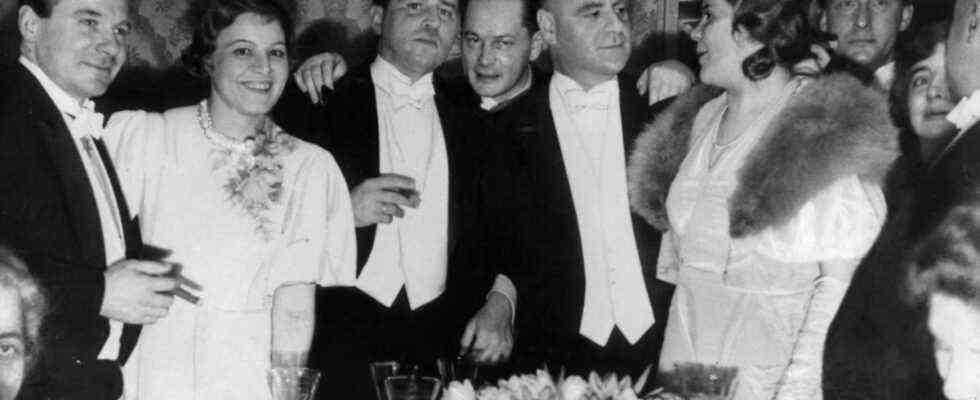

It all begins with the press ball on January 28, 1933, shortly before Reich President Paul von Hindenburg appoints Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor. Wittstock made the playwright Carl Zuckmayer, superstar of the Berlin theaters and darling of high society, the main actor of the ball night. Zuckmayer himself told of this “last dance of the republic” in his memoirs “As if it were a piece of me”. Wittstock drew plenty from this source and skillfully linked the material with the perspectives of the other guests – Klaus Mann, Kadidja Wedekind, Erich Maria Remarque.

Uwe Wittstock lets his heroes approach the catastrophic events of this terrible year from different directions.

(Photo: Marco Destefanis / imago / Pacific Press Agency)

The almost cinematic editing technique, the scenic transitions and the many “celebrity sightings” show this above all: This is where the literary elite of the declining republic meets and – this is Wittstock’s basic fable, so to speak: they all knew each other – suspects this highly networked society of the successful , knows or suppresses what is in store for them now. Each of them is his own novel, but fate drives them together into a community – which will very soon found a very real colony of “hopeless tourists” in the small French coastal town of Sanary-sur-Mer, as Walter Mehring called them Emigrants.

Wittstock lets his heroes approach the catastrophic events of this terrible year from different directions. The drinker Hans Fallada and the hard-drinking Ernst Rowohlt find out about the Reichstag fire during a visit to a restaurant, only their wives can prevent those who have escaped from going to the Reichstag and “helping Göring cook,” as Rowohlt roars. A society meets in the house of Georg Bernhard, the editor-in-chief of Vossischen Zeitung, the francophile republican Heinrich Mann is one of them, as is the francophile aristocrat Harry Graf Kessler, whose diaries are among the most important testimonies to the socio-political moods of those years. Another group meets regularly in the apartment of the sporty novelist and reporter Bernard von Brentano. It includes Bert Brecht, whose plays have already been banned from the stage, and Leonhard Frank, the proletariat dandy, whose literary success has earned him not only admiration but also distrust.

Occasionally one would have liked a little reference to the sources in the text

The first escape stories begin, which Wittstock tells in a captivating and poignant way. Alfred Kerr, who is sick with the flu, takes the first warning seriously and flees to Prague. The courageous Heinrich Mann, who with the help of his wife Nelly travels to Strasbourg via Kehl and does not want to feel like an emigrant in France at any price. Heinrich Mann had previously been removed from his post as President of the Poetry Section in the Prussian Academy of the Arts. Hardly anyone dared to defend Mann. The outsider Gottfried Benn, whose membership Mann had previously operated, works with cold anger to bring the academy into line. When Benn finally realizes that the nobility of the spirit, at the top of which he counts himself, should now consist of wretched Nazi scribes like Kolbenheyer, Johst and Blunck, he turns away in disgust.

The German doctor and writer Gottfried Benn at a microscope.

(Photo: DB / picture-alliance / dpa)

Uwe Wittstock describes all these processes in the tone of contemporary witnesses, while also freely adopting one or the other literal formulation from other works, all of which are mentioned in the appendix. Nevertheless, one would occasionally have wished for a small reference to the source in the text. The atmospheric density and the affection that Wittstock has for his, let’s call them calmly: Developed characters, make his book a kind of empathic historiography. There are leading actors like the Mann family with their very different temperaments and the fate of emigrants. And there are secondary actors like Oskar Maria Graf or Else Lasker-Schüler. In between are messages from the Berliner Tagblatt and the Vossischen Zeitung, which report on the bloody fighting between communists and the SS and are supposed to document the explosive underground of these weeks and months.

In these descriptions of sudden twists and turns and obscurations, we like to read our fears and experiences today. Wittstock does not strain such analogies too much, but he does not rigorously reject them, perhaps at the request of the publisher, who hopes that this will increase the importance of the book that the book does not need. Many facts, writes Wittstock in his foreword, show parallels to our present: “The growing division in society. The constant outrage on the Internet that drives the wedge ever deeper.” In addition, there is the perplexity of the middle class, growing hatred of Jews and the uncertain economic consequences that would arise from the Corona crisis.

Apart from the fact that there was no Internet in the Weimar Republic, there is hardly any risk of reading Wittstock’s story of that literary winter as an allegory of our present. “February 33” is the story of a terrible expulsion of the German spirit and an attempt to destroy it completely. Because he didn’t succeed in the end, the Manns’ books, the stories by Anna Seghers, the reviews by Alfred Kerr and – recently again – the novels and memories of Gabriele Tergit are irrevocably part of our happy reading life.

Uwe Wittstock, February 33, The winter of literature. CHBeck Munich 2021, 288 pages, 24 euros.