On the afternoon of August 30, 2002, three SZ editors made their way to the Hofbräuhaus, where they had an appointment with the writer Carl Amery and the CSU politician Peter Gauweiler. After a witty chat, the group moved on to the rooftop terrace of a nearby hotel. At that time, a federal election was imminent, and it was becoming increasingly clear that a Bavarian candidate (Edmund Stoiber) could actually become Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany.

So it made sense to discuss Bavarian sensitivities that Friday, and not least the myth that surrounds the old Bavarian country. After a while, when the sun began to sink fiery red on the horizon, dozens of long-legged mannequins suddenly stalked around the pool on the roof terrace. Rarely has the glitter of the fashionable world of fashion and the simple Bavarian wisdom come closer than in that hour of sunset high above the roofs of Munich city.

Of course, this coexistence of apparently irreconcilable phenomena fitted into Carl Amery’s world view. His novels and worlds of thought were bursting with discrepancies, which he nevertheless squeezed together with virtuosity. For example, in the novel “An den Feuern der Leyermark” he simply let the Bavarians, who had returned home from the German war of 1866 as losers, simply win against the Prussians, and then thoughtfully portrayed how the course of the world was in shape in this case of a somehow liberal Bavarian principle would have continued.

The passion of the admonisher, who was mentally way ahead of his time

Amery belligerently laid out the essence of his thinking during the discussion at the hotel pool. As always, the passion of the admonisher, who was intellectually far ahead of his time, bubbled within him. In fact, he had already foreseen catastrophes like those at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant when others were still shaking their heads in bewilderment. “Now he’s exaggerating,” he thought at some point in the 1970s, said former Munich mayor Christian Ude later, after Amery had warned in an article in the SZ that “the livability was a factor in view of the “ruthlessness of the nuclear industry”. of the earth” at stake.

When it came to preserving creation, Amery was rigorous. Again and again he approached leading politicians that they should “reduce the huge fleets of private transport by offering sufficient public transport”. In the early 1980s, as a founding member of the Green Party, he had helped people to sacrifice God-given creation for scandalous profit without batting an eyelid. He didn’t get a lot of attention. “We were considered slackers and nothing else,” Amery said at the poolside discussion.

The CSU had ignored him for a long time, for them he was something of an antichrist and a Bavarian nag. But Amery was undeterred. In the conversation, he emphasized (as did Gauweiler) that he considers himself conservative. Others called him a conservative rebel and a left-wing Catholic. In the 1960s, hardly anyone was as harsh on the church as he was. Nevertheless, he remained a Catholic, even if the official church would have liked to get rid of him.

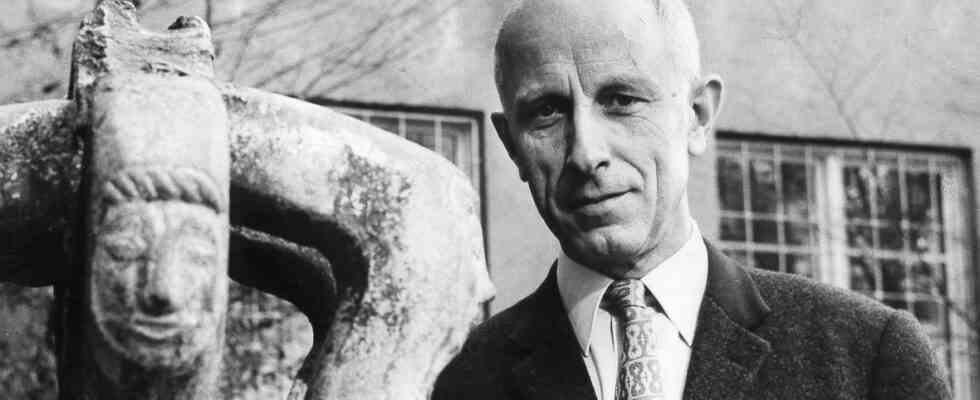

The many tributes that Amery, who died in 2005, is receiving again these weeks on the occasion of his 100th birthday make it clear what an exceptional figure he was. Even if he didn’t make it easy for anyone. Not even the Greens, who also didn’t know much about him, for them he remained a dyed-in-the-wool Bavarian, who came across as strangely baroque even without belly and bull’s-mouth. When the Greens celebrated their 25th anniversary in 2005, Amery teased them with a warning that they should fundamentally reconsider their political orientation.

He suffered at his homeland precisely because he loved it so much. That makes Amery’s view of Bavaria valuable to this day. The journalist Rüdiger Dilloo once recalled the writer Ruth Rehmann, who in 1966, after an ironically colored SZ report about a veterans’ festival in Chiemgau, had been threatened with abuse, rape and drowning. In her distress, she asked Carl Amery for advice: “What should I do, go to the police?” “It’s useless,” Amery said to her. “Either you write a story in mirror and emigrate from the Chiemgau. Or you call your Mei!”

His school days in the episcopal cities of Passau and Freising, his years in the war and in captivity, his literature studies in the USA, his membership in Group 47, his presidency of the PEN Club, his secluded life in Hirschbichl in the Ebersberg district, all of that formed him into one of the most original writers of the post-war period and, as it were, into a living contradiction: left-wing Catholic and Ur-Bavarian, rebel and conservative, dreamer and realist.

The codes of his thinking are not always easy to decipher

The codes of his thinking are not always easy to decipher, least of all in his novels. The literary scholar Reinhard Wittmann says that one has to make an effort when reading Amery’s texts. But those who know Bavarian history well back to the 18th century, plus literary pearls such as the books by the satirist Anton von Bucher (1746-1817), will find Amery’s exuberant language a pleasure. “He was an incredibly free and independent spirit,” says Wittmann.

A solitaire who was more concerned with the question of how the earth could survive under the burden of overpopulation, scarcity of resources and environmental destruction. Out of this threat, Amery developed the timeless paradox: “Man is only the crown of creation when he knows that he is not.”

It was already dark when, at the end of the conversation at the hotel pool, Amery named his heart’s desire: a Europe of regions. “Because we’re going to be moving towards something far worse than anything we’ve known before.” Humanity, he suggested in his usual cryptic style, would soon be left with only the options of life and death.