The hair has become whiter, the handshake has become softer and the lines around the eyes have deepened a little. Otherwise, Georg Schrenk has hardly changed since the Dillinger Helpers’ Circle was founded almost eight years ago. Just like with meetings in 2015, the 73-year-old can still talk about the details of the right of residence and talk about the major political lines in the very next sentence. “Apart from the climate crisis, escape is the greatest challenge of the century,” he says in one of these moments.

If you visit Schrenk these days in his sparse office in a Catholic rectory on the outskirts of town, it sometimes seems as if time has stood still in 2015. Hundreds of thousands of people in Germany are once again seeking protection from bombs and terror – this time they are fleeing the war in Ukraine. District administrators and interior ministers are again warning of excessive demands. Gymnasiums are being converted into emergency shelters again.

And yet a lot is different this time.

Back then, when the so-called refugee crisis hadn’t really started, the retired army colonel set up a group of volunteers as a town councilor in Dillingen, Swabia. In the years that followed, around 120 active people worked hard to ensure that the state authorities in the city of 20,000 did not collapse under the high number of refugees.

Schrenk and his people organized official visits and German courses, and supported people from Syria, Afghanistan and Eritrea in their search for housing and jobs. They organized cooking evenings, lectures, political debates. Schrenk, a man of robust nature, structured the help like the commander of a regiment: disciplined, direct, if necessary confrontational. Always effective.

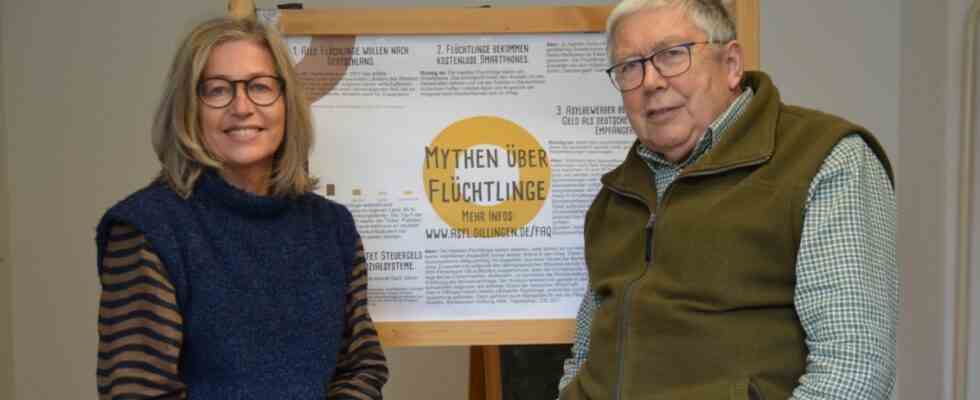

The commitment of the Dillinger troops was considered exemplary throughout Bavaria. The then Federal Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (CDU) personally honored Schrenk for his commitment in 2020. “I’m a convinced soldier,” Schrenk said, wearing a plaid shirt and an olive-green waistcoat, at a meeting in December. “And as such, I’ve learned to complete an assignment.”

The only problem is that many helpers have since left the flag. Of the 120 active people in Dillingen, only about 30 are left today. “There is a lot of tiredness,” says Schrenk. Many of the supporters from 2015 are now so old that they are no longer able or willing to help. One of his active members is now 87. Young people have hardly moved up. There is also the feeling that one’s own work is not valued. “In many authorities, we tend to be perceived as troublemakers,” says Schrenk. That wears me down.

Everywhere in Bavaria, volunteers now have the impression that they have embarked on a never-ending mission that is rarely rewarded. Many give up. The association “Unser Veto”, in which groups of helpers from all over Bavaria are organized, recently published a survey with 225 participants that summarizes the withdrawal in figures: Two thirds of those surveyed stated that the number of helpers had increased since 2021 decreased while the tasks increased. “Many thought in 2015 that they only had to support refugees until the state took over these tasks,” says Joachim Jakob, chairman of “Unser Veto”. Eight years later, the volunteers are disillusioned and frustrated.

When you talk to refugee helpers these days, you almost have the feeling that a collective burnout has taken hold of the groups. “A whole series of helper groups has already dissolved or is in the process of being dissolved,” says Jakob. In the district of Dachau, where he himself works on a voluntary basis, the number of active people has fallen from almost 1,000 in 2016 to just 168, according to his own survey. Jacob also mentions aging as one of the reasons for this. “During the Corona crisis, older people in particular withdrew for fear of infection,” he says. Many have not returned. But that’s not the only explanation.

Barbara Brüning is one of those who keep going. The 64-year-old teacher is one of the hard core of the refugee helpers in Dillingen. She can also list many things that frustrate her about volunteering, for example the restrictive interpretation of the asylum laws in Bavaria. She is annoyed that the Free State recently deported people who were required to leave the country, but who would have had the prospect of staying with the right of residence decided in the Bundestag at the beginning of December. “Other federal states had stopped these deportations long ago,” says Brüning. “But Bayern kept going. That’s frustrating.”

“Our voluntary work is hindered,” says a helper from Dillingen

The helper says these words one day after Bavaria’s politicians also used the day of honorary office to praise civic commitment in the highest tones. “But this commitment keeps turning,” says Georg Schrenk in his Dillingen office. Barbara Brüning, who is sitting across from him, is even clearer: “Our voluntary work is being hindered.”

Every refugee helper can often report conflicts with the immigration authorities, she says. From a simple driver’s license to a work permit to deportation, Brüning feels that caseworkers often make harsh decisions rather than using their leeway in specific cases. “Fighting against it takes a lot of energy,” she says. Often the battle is lost.

The current treatment of war refugees from Ukraine shows that there is another way. Thanks to an EU directive, they do not have to undergo time-consuming asylum procedures, have better access to the social systems and are allowed to work quickly. Brüning thinks that’s a good thing, but she would have wished that all refugees had been made easier. “But even this small hope was dashed,” she says, looking at a loss.

The burnout of active people can also be scientifically proven. Researchers from the Center for Flight and Migration at the University of Eichstätt recently published on the role model of refugee helpers and found explanations for the frustration. The volunteers often become “fill-ins” to compensate for the lack of full-time positions. This leads to a “role conflict, in which those involved are often entrusted with responsibilities and sometimes also demand them, the extent of which corresponds more to a full-time job and often ends in feelings of being overwhelmed and frustrated,” says the article.

According to experts, the refugee helpers have become more professional – but also politicized

Overall, refugee aid has become more professional over the years, according to the authors, but also politicized. “Asylum policy, which is perceived as restrictive, personal experiences and right-wing populist propaganda against refugees ensure that the motives for the commitment are changing.” At the beginning of the engagement, it was often about “learning something new about other cultures”, but now the focus is on the will to shape society.

“What would have happened if we hadn’t existed?” Brüning replies when asked why she isn’t giving up. “Chaos.” And Schrenk also points to the successes of the commitment, which have been achieved in spite of all the disappointments in recent years. “About 80 percent of the recognized refugees that we have looked after are in work.” Some are now active in the fire brigade, others in the football club, and seven refugees have started studying. “The children are also well on the way to arriving here,” says the 73-year-old.

Schrenk predicts that the winter will again bring with it great strains. Many Ukrainians have to leave their bombed-out cities because of the cold, and container emergency shelters are already being planned in Dillingen, he says. However, his shrunken team can only help some of the newcomers. “Fortunately, the Ukrainians have good networks in Germany and get along well here.”

And how long will he keep going? Schrenk answers this question, typically a soldier, frankly: “If there is no executive board capable of acting at the next election, I will propose the dissolution of the association in the coming year.” At some point it was also time for him to “resign to the second or third rank”. Silence fills the unadorned office, then Barbara Brüning takes the floor. “And if there is a board – do you make the chairman again?” Schrenk smiles and looks meaningfully over the rim of his glasses. “I’ll have to ask my wife first.”

facts and figures

218,000 refugees have already come to Bavaria this year. According to the Ministry of the Interior, the number is “already above the level of 2016” when the so-called refugee crisis reached its peak. Around 125,000 people are currently being accommodated in state accommodation, which corresponds to an occupancy rate of around 95 percent. In more and more districts, gymnasiums are being converted into emergency quarters for the winter, for example in Neuburg an der Donau, Geretsried, Wolfratshausen or Miesbach. The Ministry of the Interior does not record how many emergency shelters there are currently in Bavaria.

However, it assumes that the situation will not ease in the coming months. That is why corona vaccination centers are also being checked for their suitability as refugee accommodation. In addition, the ministry recently revoked its guidelines on the type, size and facilities of shelters. These give each resident an average living space of seven square meters, and no more than four (maximum six) people should be accommodated per room. In certain cases, the suspension is intended to accommodate more people in the facilities, and the ministry speaks of “more effective use” through redistribution and densification. This should be done “taking into account social aspects”.