Gregor Stolarski is constantly involved with stones, for example with the reddish sandstone of the old Nuremberg city wall. Sometimes with marble, shimmering, “white as sugar,” says the engineer. He’s a friendly person and knows he can quickly wax lyrical about the complexity of any rock stratum, so he jumps straight to vivid comparisons. As an expert from the Landesgewerbeanstalt LGA, he repeatedly receives inquiries for investigations.

But the one from Berlin about two years ago sounded unusual: Brazilian, azure-blue stone, one of the most expensive in the world, is on the sea route to Europe. The size and weight of the cuboid, about four meters high and weighing almost 30 tons, are also record-breaking. In addition, you only have a few months and the pandemic is jeopardizing the schedule. Would Stolarski examine the giant cube? “The firmness,” he says in a video call at the end of January, “was completely uncertain.”

The man from Nuremberg is an undisputed expert in his field. He rarely has anything to do with international artists, in this case Alicja Kwade’s Berlin office. Kwade is listed among the top 100 artists in the world, exhibits in the USA, in Europe. Known for installations and very expensive, elegant sculptures, she has previously worked with heavy forms, with copper, gold and mirrors.

Before Stolarski, an engineer had refused the order, the stone was simply too big to be able to measure deep enough. But when, he thought, do you ever come across such an old, quartz-rich sandstone? The “Macaúbas Do Azul” is 1.2 billion years old. For the first time, such a massive cuboid was cut from a Brazilian quarry. He agreed.

Cut in Brazil, ground in Poland, tested in Bavaria: The azure blue cuboid still weighs about 52 tons, later it becomes the 24-ton “Solid Sky” sphere.

(Photo: LGA/oh)

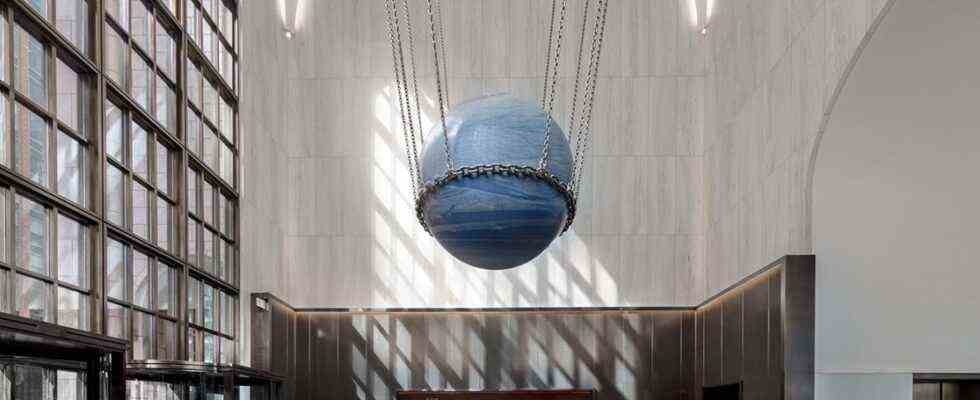

Today the work is hanging, having survived the transport from Brazil across the Atlantic to a Polish workshop and back across the sea to New York unscathed. It has been hanging in the foyer of a luxurious office building in Manhattan as a sphere entitled “Solid Sky” since the end of 2021. Huge, sleek, shiny, hauntingly blue – and as heavy as about 14 cars.

Nuremberg rock tester Gregor Stolarski at work.

(Photo: LGA/oh)

In addition to Stolarski in Nuremberg, engineer Roman Auer received an inquiry in Rosenheim. For weeks he then “calculated measurements and weights and moved them back and forth” on the PC, then tests with his team followed. While the Nurembergers brooded over the nature of the stone, the Rosenheimers were responsible for another crucial part of the work of art: the suspension.

At the chain manufacturer “Ketten Bäume” in Rosenheim, they specialize in exactly that, stainless steel strands, for example for nautical purposes, for large anchors. But the work of art went beyond the usual portfolio: XXL chains were needed to hold the planned 24-ton sphere. “That was the challenge,” says Auer, “to combine the technical requirements with the visual wishes of the artist.”

They made ten strands and a “braid” on which the ball lies. Particularly tricky: the nodes between chains and wrapping. “There’s a lot of strength there,” says Auer on the phone. Although it would be customary to weld them mechanically, they welded them by hand to be on the safe side with the optics here as well. In order for everything to produce a coherent overall picture, the chains should be reflective, so some of them were also polished by hand.

Made in Rosenheim: The steel chain construction by Roman Auer (left) and his team before being transported to the sphere.

(Photo: Company Chains Forests/oh)

It was all the more impressive to see the ball, chains and the actual dimensions during the test hanging, says Auer. After endless planning and testing, all theory had found its way into practice.

Holds what it is supposed to hold: Kwade’s ball, 24 tons, in the chain construction co-produced by Auer.

(Photo: Company Chains Forests/oh)

And that was stored in a workshop of two Franconian-Polish stonemason brothers in Ciasna, Silesia. Kwade had worked with them before, and that’s where the paths of Stolarski from Nuremberg and Auer from Rosenheim ultimately crossed – albeit at different times. Stolarski had previously traveled to take samples. Because before the people of Rosenheim could put on the chains, the stone had to be ground into a ball. “But the question was,” says Stolarski, “what happens when the stone is cut? Does it crumble away on the lathe or does the natural cement hold up?”

Stolarski drilled samples from the block. What was later to become the round had to remain intact, it was only allowed to be drilled for the later suspension points. Again and again Stolarski and his team examined the material in Nuremberg, where they have the appropriate laboratory equipment. They tried to see inside the stone. They pulled on the samples with machines, exerted pressure on them, looked for air spaces and weak points in the ancient, delicate layers of material. After a few extra shifts, they were 95 percent sure the stone would hold. Three months later, the cube was ground into a sphere. And nothing had crumbled, nothing broken.

At the turn of the year 2020/2021, the stone went on a journey again, this time to New York. They trembled to the end, says Stolarski and grins at the camera. Under no circumstances should the ball get scratches, and then there were also winter storms during the crossing.

It’s chained up for packing and then across the Atlantic to New York: “Solid Sky” is later hung in a foyer.

(Photo: LGA/oh)

The ball has been hanging at a height of three and a half meters ever since, and hymns of praise for Kwade’s coup were not long in coming. But why Bavarian expertise for the project? In the artist’s Berlin office, one does not receive any personal information from Kwade, but does hear that they appreciate the openness of manufacturers in Bavaria towards art projects.

According to their own information, Chain Forests is one of the few companies that can handle such projects. And the LGA in Nuremberg, for which Stolarski works, obviously has a reputation as one of the oldest engineering institutions in Bavaria. A reputation that is also defended in New York, says Stolarski and grins again, right down to the engineering office there, to which he always sent his reports.